Riva Lehrer’s New Memoir Captures Stories of Stigma

Riva Lehrer (SAIC 1993–95) has always been interested in the outlier. An assistant professor, adj. at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), Lehrer’s work—which focuses on transforming mainstream views of stigmatized identities like disability—has consistently garnered recognition and awards. Most recently, the longtime faculty member was honored by the Ford Foundation and Andrew W. Mellon Foundation as one of 20 Disability Future Fellows.

Lehrer is best known for her paintings that tell the stories of people who have been ostracized for their disability or sexual or gender identity. However, this fall, she decided to tell a different story—her own.

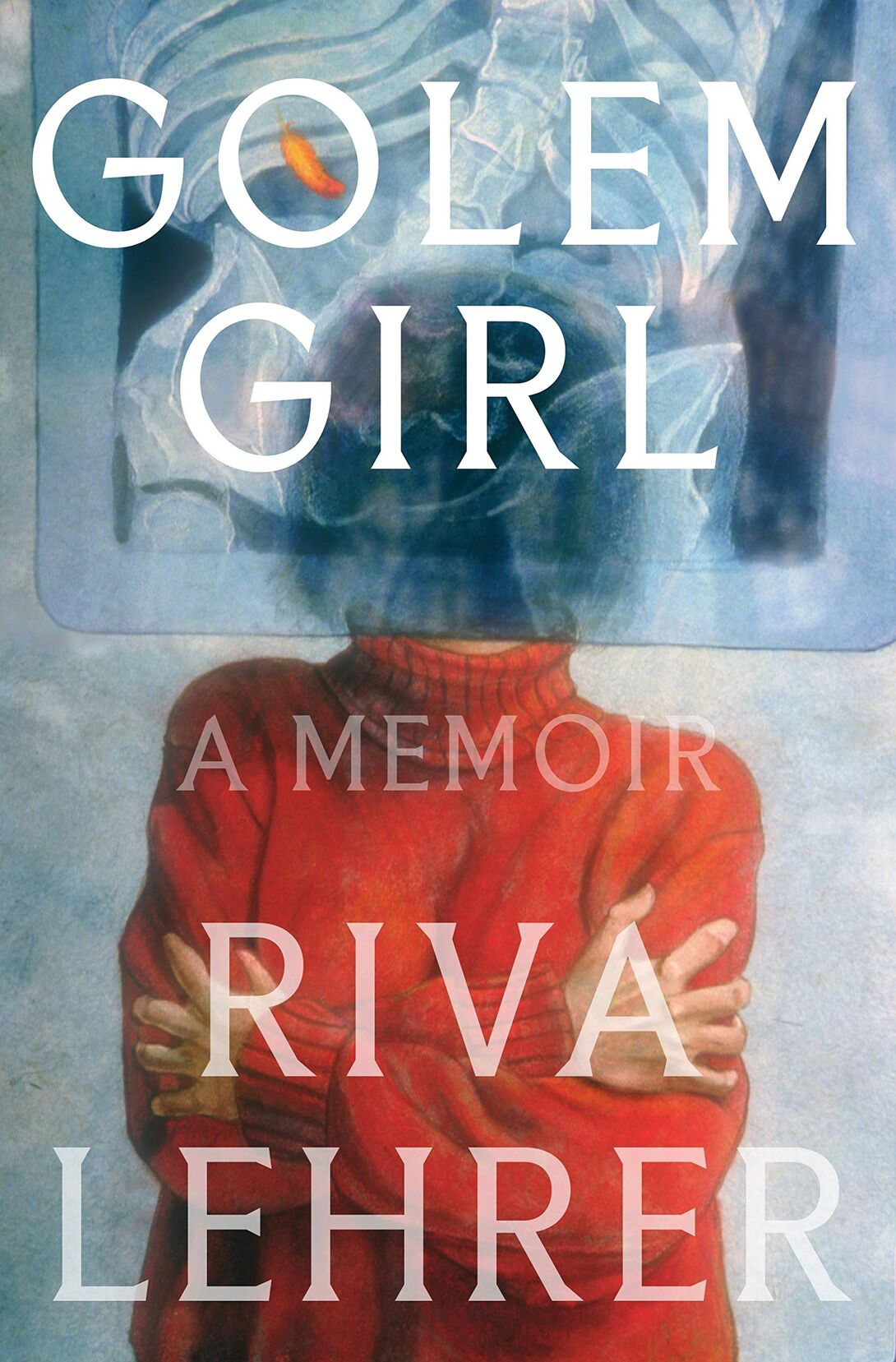

Lehrer’s new book Golem Girl is an autobiographical memoir that narrates her experience growing up with spina bifida. When a group of working artists, writers, and performers invites her to join them in building Disability Culture, everything changes. “Their work . . . rejected old tropes that defined us as pathetic, frightening, and worthless,” explained Lehrer in the New York Times. “They insisted that disability was an opportunity for creativity and resistance.”

The book launched on October 6 and has already received rave reviews, including a spotlight on NPR’s Weekend Edition. In celebration of Golem Girl’s release, we chatted with Lehrer about her first venture into memoir writing and her experiences as a teacher and maker in an ever-changing world.

What gave you the inspiration to put your story into words and share it with the world?

My portrait work begins with interviewing people about their lives and about the influence of their embodiment on their work. I would spend months getting to know somebody before we started, and the best way to get the real truth from someone is to be honest yourself. I would find myself trying to match their honesty. After a number of years, I ended up with a lot of intersecting stories, between their lives and my own.

What was the experience of writing a novel like?

I have almost no background. I attended a couple of extended workshops and that’s almost the entire history of my training as a writer. The contrast of that inexperience and being a painter who’s been training for 40 years, it was like whiplash. I would be bopping along on something in my studio and I’m like, “Okay, now I need to do this. Now I need to do that, and here’s the struggle here.” Then I’d go to the computer and be like, “Uh. I don’t know how to do this. At all.”

It seems to have all come together—the reviews have been incredible!

I am pleased and surprised. What’s nice about the School’s environment is the fact that it’s so interdisciplinary. There’s this aura of “don’t nail yourself into one box”; it’s one of the great glories of the School of the Art Institute—they want you to explore all of yourself.

You’ve said your book is in two parts: the first growing up in a time without disability rights, and the second about the discovery of Disability Culture. What has—or hasn’t—changed in the larger world during these two chapters of your life?

When I grew up, disability was only discussed as a medical issue—and a very personal one—that had no societal or political meaning. You had a “deformity,” and the point was to try and fix it. There is a Disability Culture now, and an understanding that disability, and other forms of embodiment, often have more overlapping congruences than not. A lot of people don’t know Chicago is one of the centers of Disability Culture in America.

What hasn’t changed is pretty obvious. As soon as COVID-19 hit, our government told us that we were disposable. Even though that’s gotten quieter, it hasn’t gone away. People with impairments—disabilities—that’s what a pre-existing condition is. Being disabled isn’t whether or not you have a wheelchair, it’s whether or not something exists in your body slash mind that affects the way you live and the choices you get to make.

Along those lines, how has the pandemic shaped your current reality as a teacher and an artist?

I am trying various methods by which to be a portrait artist, but I can’t have anybody in the studio and that is interesting in the extreme. I’m working over Zoom. I’m collaborating with photographers out of town. I have at least four different strategies as I try to deal with distance. I have a show at Zolla/Lieberman Gallery that reflects a few of these strategies, which we called Pandemic Portraiture.

In terms of teaching, I am teaching remotely. At times it is frustrating, but I’m hopeful. One thing that I hope comes out of the pandemic is that we’re now in a place where the School community is having to think about everyone’s physical safety and everyone’s access; everyone is vulnerable. As soon as the easy way is gone, you really have to think your way through your options. I’m hoping this sort of cumulative thinking and reinvention might lead to a more accessible School in the long run.

What’s one thing you want your readers to know about you and your work?

On one hand, my focus is on impairment and Disability Culture, but I’m deeply interested in stigma. How the world tries to dislocate us from our bodies and then shove us into approved structures. When peoples’ perceptions change, it’s often that the arts open them up first and then they can hear the politics. I don’t know how often it happens the other way around—I think something emotional happens that changes their views, and then they want to understand the implications. The politics. Disability Culture does change the world. It really does.