Our Kind of Town

SAIC artists empower Chicagoans

by Jason Foumberg (MA 2006)

For more than a century, SAIC has possessed an ethos of civic engagement that compels its artists, designers, scholars, and educators to create work that extends beyond the studios and classrooms and into the diverse communities of Chicago and beyond. In 1899, faculty member Lorado Taft sparked a conversation on what work women should do for allowing his female students to help create a fountain in the form of nude female figures. In the 1940s, Art History faculty Helen Gardner and Kathleen Blackshear (MFA 1940) placed the art of Africa, Aboriginal art, and Islamic art on the same level of the European Renaissance—a radical idea for the time. These early examples set the stage for faculty and alumni to continue to engage with the critical issues of their time.

Here are five moments throughout our history when SAIC artists, designers, scholars, and educators made a difference with their work.

Art School at Jane Addams’ Hull-House

SAIC alum and faculty member Enella Benedict, after her 1890 graduation, founded an art school at Hull-House, a settlement home created by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr in a densely populated immigrant neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. Benedict moved into the home in 1893 during the World’s Columbian Exposition. She expanded the studios to appeal to all ages and brought in other teachers and artists-in-residence and held exhibitions. Her classes offered an opportunity for all people to exchange ideas and create art together. At the same time, she remained on the faculty at SAIC, serving as a bridge between the two institutions. She lived and taught at Hull-House for more than four decades, longer than any other resident aside from Jane Addams herself.

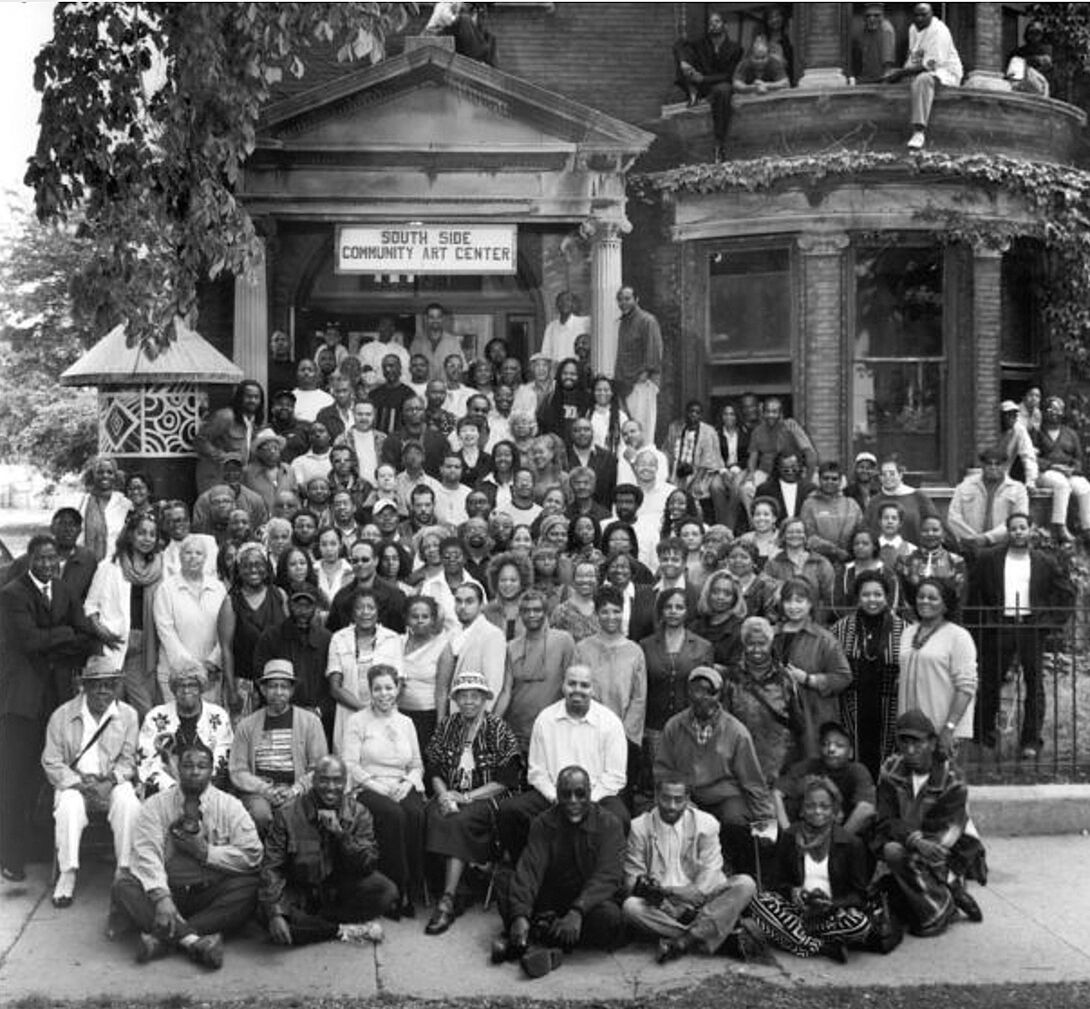

South Side Community Art Center

In 1940 a group of artists led by SAIC alum Margaret Burroughs (BA 1942, MA 1948, HON 1987) founded the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC), the first African American art center in the United States, with help from President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration program. Burroughs, who later went on to found Chicago’s DuSable Museum of African American History, left a deep impression on the city not only through her artwork, but also in her role as a dedicated community advocate of Black culture. She proudly said her museum was started by “ordinary folks” to signify that anyone could build a museum if it needed to exist, if certain historical truths had been lost or obscured. The museum maintains its connection to SAIC as faculty member Lee Bey was recently named its director. Today, both DuSable and the SSCAC continue to serve Chicago.

Wall of Respect

A new institution need not always have four walls; sometimes it can have a single powerful wall. As the 1960s saw massive political and social shifts in Chicago, a South Side mural came to be known as the Wall of Respect. It featured paintings of Black heroes like Nina Simone and Muhammad Ali. SAIC students and alumni in the AfriCobra (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) movement contributed to the Wall, which became an icon of racial equality and Black greatness and a gathering site for activism. The Wall of Respect is considered the spark of Chicago’s public mural movement.

A Lived Practice

In fall 2014, SAIC mounted a three-part program comprised of a major exhibition, series of five publications, and conference led by Executive Director of Exhibitions and Exhibition Studies and Professor Mary Jane Jacob. Collectively called A Lived Practice, it asked, “Can a life practice be an art practice, and can an art practice be a life practice?” Jacob, a key scholar and practitioner of social practice, says, “There is an ethos at SAIC that artists do not just critique culture, but they can change it.” The Chicago Social Practice History Series, the go-to handbook for today’s artist-activists that emerged from this program, will publish its sixth volume this fall titled Talking to Action and dedicated to Latin American perspectives.

SAIC at Homan Square

Two years ago this fall, SAIC opened a new space for artists in Chicago’s Homan Square community. Housed within Nichols Tower, the satellite classroom offers SAIC faculty, students, and alumni a place to engage in arts and civic literacy with residents of the city’s North Lawndale neighborhood, a community working to redevelop itself from years of poverty and violence. Free art classes are offered to local residents on topics from how to use big data to combat street violence to urban farming. SAIC students take elective courses in the refurbished art deco building—the original 1906 Sears Tower— on topics like Lavie Raven’s University of Hip Hop. This fall will debut Miguel Aguilar’s (MA 2011) year-long Spray Runners: Street Art and Body Training class that blends hyper-local mural history with jogging.

In this space, SAIC aims to engage neighbors, artists, and scholars in collaborative processes to identify issues, promote public discourse, and catalyze social change, continuing a tradition more than a century old.