Mineral Point: Becoming Part of a History

By Carlos Antonio Piñón (BFA 2017)

On a crisp October morning, my SAIC 150: Repeat Transmissions class set out to visit Mineral Point, Wisconsin—a Midwest town whose history collides with SAIC alum, Edgar Hellum.

Led by SAIC faculty members Mark Jeffery, Nick Lowe, and Lisa Stone, we began our research at the Mineral Point Library, where we freely sifted through the town’s archival material. “Every archivist’s worst nightmare,” according to Stone.

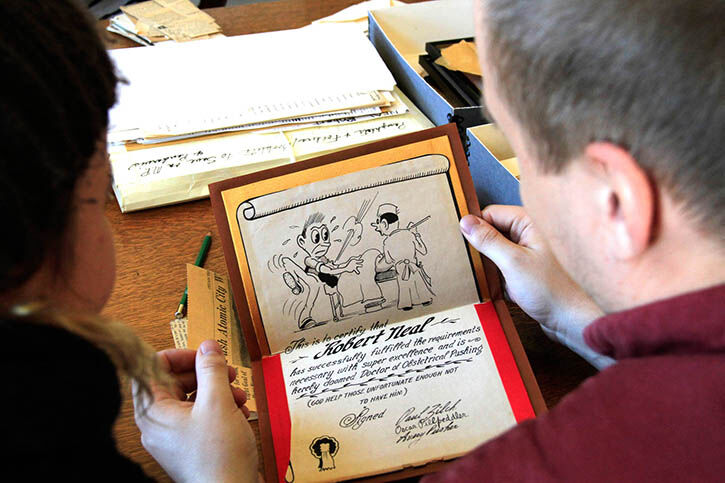

While digging through historic newspapers and letters from the 19th and 20th centuries, we came across something strange—a hair sample that belonged to Bob Neal, a Mineral Point native and Hellum’s life partner. After our archival research, we met with SAIC Professor Emeritus Jim Zanzi and Jim Stroschein, former president of the Mineral Point Historical Society, to learn more of Neal and Hellum’s legacy.

Hellum attended SAIC for three semesters before feeling out of place. “He felt he didn’t belong there. He just felt all of the students were so talented; he was embarrassed and just couldn’t deal with them,” Zanzi said. Hellum left SAIC and returned to Stoughton, Wisconsin. A friend invited him to visit Mineral Point. There he met Neal and learned that many of the 19th-century cabins built by the town’s Cornish miners were being torn down. Hellum and Neal became partners (professionally and romantically), and they began to purchase and restore many of the Cornish buildings, which typically had low ceilings and were constructed of wood and limestone. Their first historic preservation project was a one-story stone cabin called Pendarvis.

To support other restorations, the couple converted Pendarvis into a makeshift restaurant that served local cuisine, including handmade bread and butter, plum preserves, and scalded cream. “[They were] showing the town because people had scoffed at them when they started working,” Stroschein says. “The Shake Rag area [where Pendarvis resides] was the slum of Mineral Point… You didn’t want to walk down there at night.”

Despite this, Pendarvis became a tourist destination. Betty Cass, a noted columnist from the Wisconsin State Journal, stumbled across the Pendarvis House while reporting on the Frank Lloyd Wright exhibit at the nearby county fair. Unaware of her renown, Hellum and Neal greeted her with tea and saffron cakes and discussed the philosophies of their preservation work. A few days later, the two were met with a surprise on their doorstep—a newspaper featuring “four lines of Frank Lloyd Wright and about a column and a half about little Pendarvis House,” says Stroschein.

Hellum and Neal saw their business grow as people lined up for tea at their now-famous fireplace. Inspired by the simplicity of their beginnings, the partners reduced their menu to one item, a savory Cornish pasty.

Fascinated by this story, our class was compelled to try the legendary food. We visited the Kiddleywink Pub, another building restored by Hellum and Neal, where local residents made fresh pasties for our class.

On our last day in Mineral Point, we visited the Mississippi River where we stood atop mounds created by the indigenous people of the area. Standing on the land enriched with history that predates Hellum and Neal, the Cornish miners, and the country as we know it now, we felt like a part of history ourselves, however small.

We spent the afternoon at the Orchard Lawn, another building restored by Neal and Hellum. The building’s preservation is a collaborative effort of the whole town—even the mayor of Mineral Point mows the lawn on occasion. “Certainly some of these buildings would have been lost had they not come along when they did,” says Stroschein as he strives to continue the work started by Neal and Hellum.

During our final evening in Mineral Point, we convened at the Midway Bar and Grill to talk with SAIC alumni and listen to Jim Zanzi as he recounted his days as a professor at SAIC. He spoke about class trips with Stone to Mineral Point where students had a chance to speak to Hellum before he died at the age of 96. Years after his death, as our class traveled back to Chicago, we each felt a sense of being a part of this lineage, this history, and this legacy.