A Machine for Producing Monsters

by Meg Santisi (MA 2016)

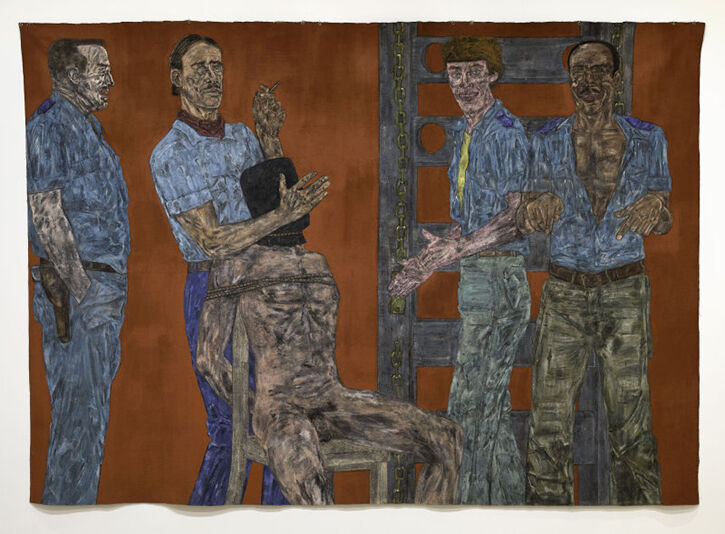

The artist Leon Golub (1922–2004, BFA 1949, MFA 1950, HON 1982) stares intently at a blank, wall-size canvas. The filmmaker Jerry Blumenthal rolls tape as Golub sets to work on his newest mural. In this 1988 film, Golub appears as a man in his artistic prime, playful, but with a deep intensity lurking underneath all that good humor. Golub begins to work. He thumbs through a meticulously organized file cabinet, pulling out several reference images cut from newspapers and magazines. One image is of a heavy-duty machine gun. Another is a horrific image of a young boy, dead on the side of a concrete road. Golub examines each image closely, and begins to sketch on his canvas. First he draws a muscular, blonde man – an almost demonic figure with a nasty stare. At his feet is a young boy, helpless and scared, about to die. The man rubs the young boy’s face into the concrete. Golub pauses, looks thoughtfully at his canvas, and finally says, “I once described myself as a machine for producing monsters, and I’m still producing them. But my production of monsters is really miniscule compared to the real production of monsters.”

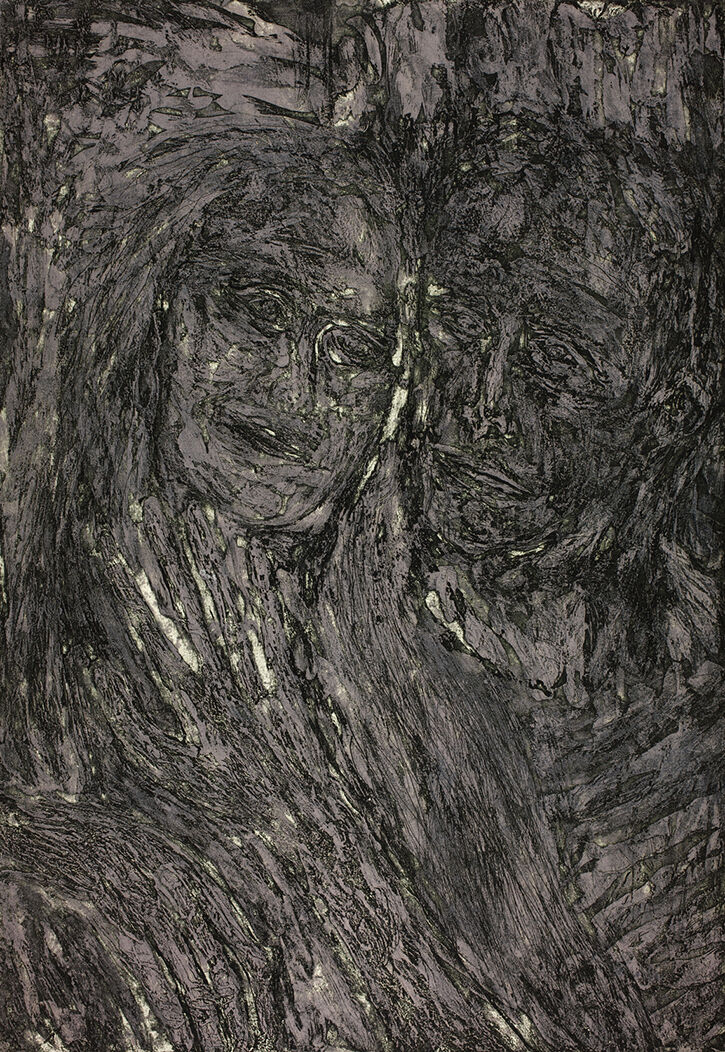

More than 10 years after his passing, Golub’s work is still haunting. Throughout his career, Golub depicted images of extreme cultural and existential power—dictators, gods, racists, and torturers dominate most of his canvases. With all this monstrous imagery, Golub represents the aggressive and violent capacities of human nature, while unmasking the cultural hypocrisies that attempt to conceal these violent urges.

As a student at SAIC in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Golub was not alone in exploring this kind of subject matter. Just after World War II, several other SAIC artists, as well as collaborators from other schools, became known for their distorted figuration, existential leanings, and mythological themes. Collectively known as the Monster Roster, the group is lesser acclaimed than groups like the Chicago Imagists, but an upcoming show, Monster Roster: Existentialist Art in Postwar Chicago, February 11–June 12, 2016, at the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art aims to shed some light on this influential group of artists.

Curators John Corbett (who is also an Adjunct Associate Professor at SAIC) and Jim Dempsey talk more about Leon Golub and the Monster Roster, and how SAIC helped to shape this group’s practice.

Who were the artists that made up the Monster Roster, and what kind of relationship did they have with each other?

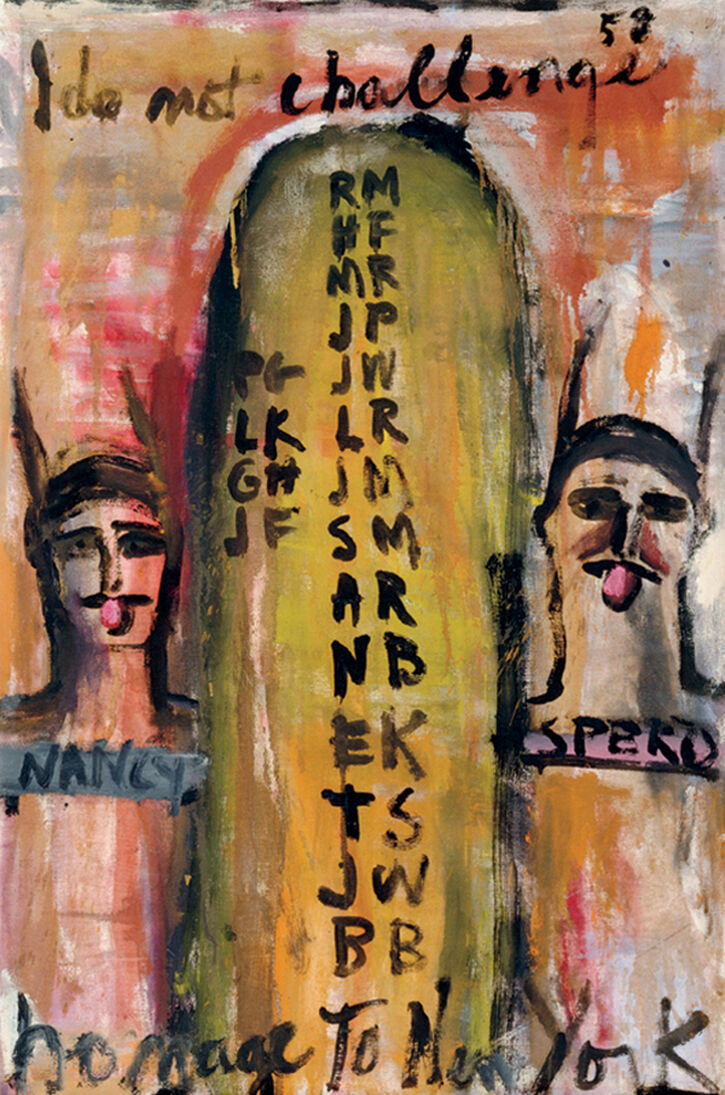

John Corbett: There was a core group of artists, people like George Cohen (BFA 1947), Cosmo Campoli (BFA 1950), Ted Halkin (BFA 1950), Dominick Di Meo (BFA 1952), Nancy Spero (BFA 1949, HON 1991), June Leaf, Seymour Rosofsky (BFA 1949, MFA 1951)—with Golub at the center point of all the activity. Golun was universally admired by these artists. The Monster Roster was identified from the outside by a former member of the group—the critic and painter Franz Schulze (BFA 1949, MFA 1950, HON 2014). He noticed correspondences between these varied artists who were all collegial, or in many cases, roommates, husbands, and wives.

In a few different interviews, Golub has described his experience at SAIC after being away at war. He described how all of his peers’ work had been indelibly changed by the scale and horror of that conflict. Do you think the Monster Roster artists were responding directly to the war?

JC: Many of the Monster Roster artists were veterans. Not all of them, but many of them. Most of the men were in the war in one way or another. They came back, and the world was changed. At SAIC, the GI Bill created an opportunity for these folks to come back and study. There was an influx of older art students, people like Golub. He was a particularly interesting guy because early on he recognized that politics were something that they he had a stake in.

Were these artists collaborating or working independently?

JC: Most of the time, they worked independently, and occasionally in small groups they were exhibited together. When Golub was nearing the end of his tenure at SAIC, he instigated an important exhibit called Exhibition Momentum [in 1948]. It involved SAIC directly because the exhibit came about as a result of many of the school’s teachers’ reactions to their students winning awards in what was called the Chicago and Vicinity Show at the Art Institute of Chicago museum. The C and V show rounded up and exhibited artists from Chicago and the greater Midwest. They gave prizes and awards—including some purchase awards in which the museum would purchase work for its permanent collection. So, many of the older, more conservative painting faculty lobbied the Art Institute to disallow student winners.

Jim Dempsey: It was probably an embarrassment that faculty could lose to a student. So somehow they convinced the Art Institute to no longer let students participate.

JC: Golub was incensed. In response he spearheaded an independent breakaway exhibition called Exhibition Momentum. It was important moment for Chicago because Exhibition Momentum invited people from all the different institutions and inclinations to come together. You had people from the Institute of Design, SAIC, Northwestern, all coming together and showing.

Thematically, it seems like all of these artists were interested in both existentialism and mythology. How do you think their philosophy extends to this interest in grander, mythological narratives?

JC: These artists were reading Sartre, Camus, Artaud, and Céline. They were interested in connections to that kind of literature and philosophy. The Myth of Sisyphus is a good parallel. The futility of that myth isn't some sort of neo-romantic notion of mythology—instead it is a midcentury notion of what that futility could be about, which is like rolling a rock up the hill and having it flatten you over and over again.

JD: And mythology shapes an idea so that anybody can connect to it. These artists were interested in finding ways a viewer could attach emotion to some kind of shared symbol or experience.

JC: I think that was very important to them at that point. Later artists, like the Chicago Imagists, eventually put that idea under a lot of scrutiny. This is an underlying difference between these two groups. The Monster Roster had some confidence in the innate goodness in humankind and, despite being shaken, still believed some unifying Jungian thing was still intact. But with the Imagists it is a totally different ballgame. They had a wholly different sensitivity to the way that signs work. The Imagists sometimes made brutal images that weren't really about brutality. Like a woman with amputated legs in Jim Nutt's early paintings—that image is both brutal and comical at the same time. The Monster Roster was much more brooding and more existentially angst-ridden.

Most of these artists studied at SAIC. Was there a single teacher or prominent figure who influenced all the artists?

JC: One teacher is common to most of the artists—Kathleen Blackshear. She was an art historian and a teacher at SAIC for a long time. Blackshear was an unusual pedagogue at that time in that she wanted her students to learn the western canon, while also paying attention to things outside of that canon. She took her students to the Field Museum, showed them so-called “primitive art,” and made them sketch in response to those works. Blackshear was somebody whose position on world art was relativistic rather than absolutely hierarchical.

Leon Golub met his wife, the artist Nancy Spero, while studying at SAIC. What was her involvement with the Monster Roster?

JC: From early on, Golub was making political paintings, and he was aware of power and feminism, and Spero was certainly keyed into questions of power, inclusion, and exclusion. From what we can tell in our research, Spero, at least retrospectively, felt left out of the group. We include her in our exhibit because her work is so clearly spiritually connected to it. The Monster Roster was a boys’ club, and despite June Leaf being there, Spero felt there was a kind machismo about the group. She was a developing feminist at that point, and surely disgruntled by the fact that she couldn’t be taken seriously, especially by curators. It was particularly difficult for an artist like Spero, a woman making some really tough, nasty, dark images. Golub was always very respectful of her independence and always supported her work.