The Art of Empathy

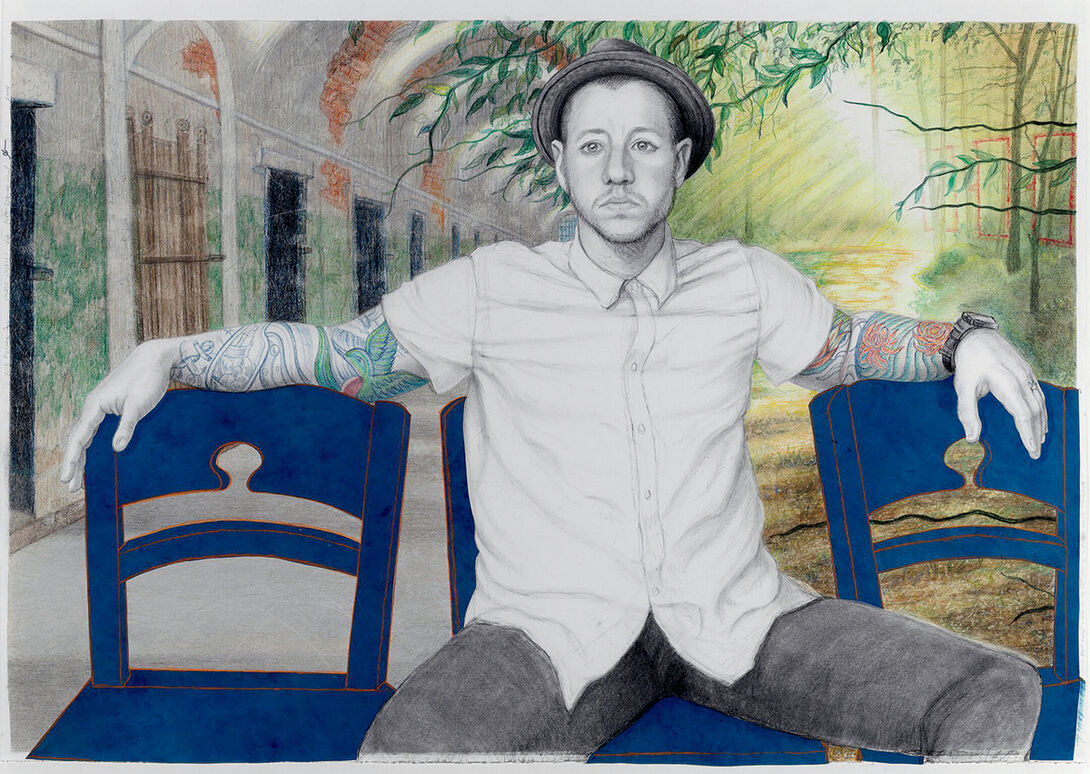

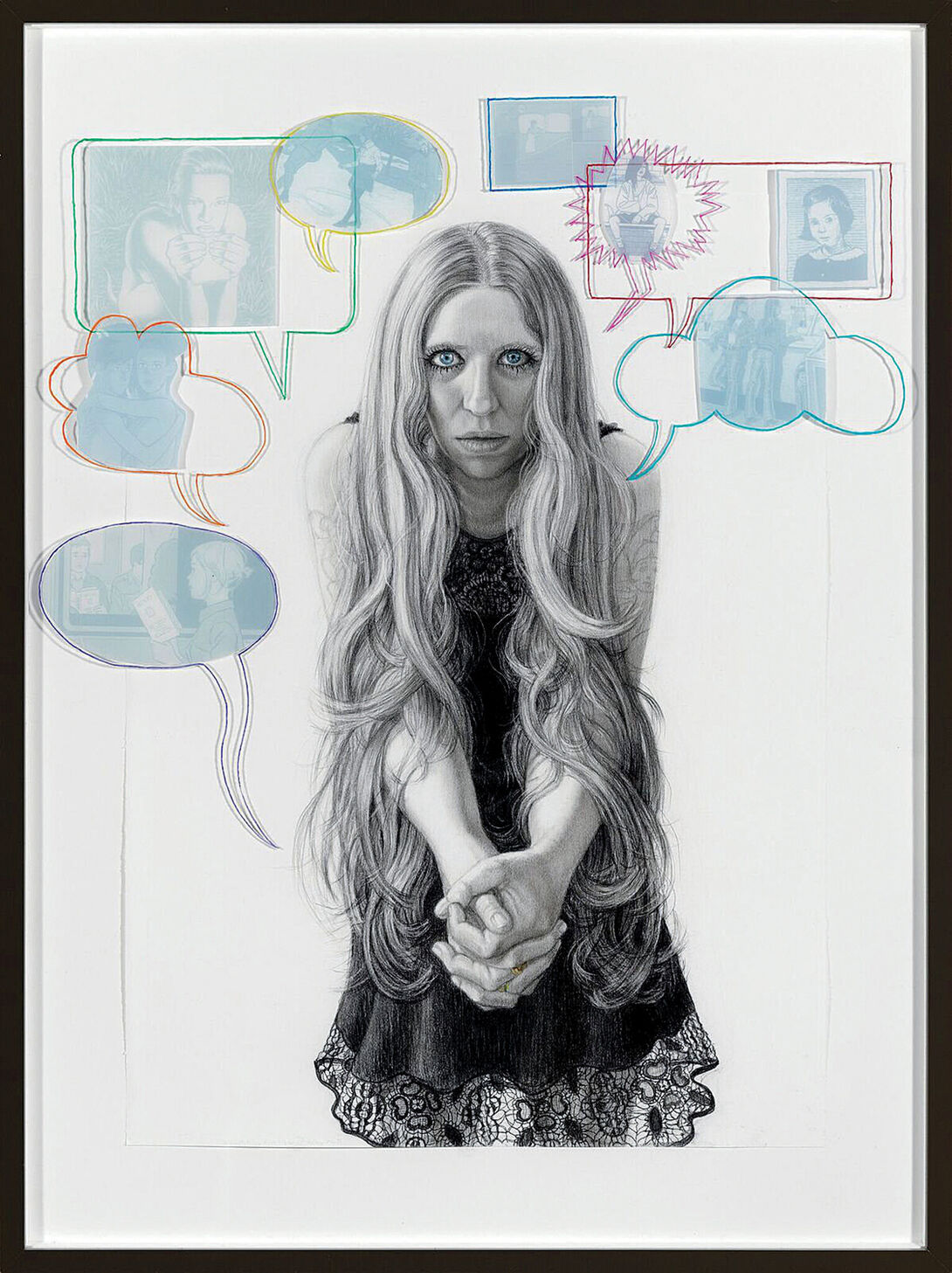

Riva Lehrer (SAIC 1993–95) is an unorthodox portraitist. For The Risk Pictures, the Chicago based artist invites into her home subjects, or collaborators, some of whom have experienced some sort of stigma—for being a transgender person or having a disability, as examples. Other collaborators do not have a disability, but are friends or acquaintances of the artist. Then, Lehrer has a system of rules. The sittings are three hours long, and after two hours, she leaves the premises, allowing her subject to do whatever he or she wants in her home, and she asks that the subject alter the portrait with her art supplies. (The subject can even destroy the portrait.) When Lehrer returns, she can respond to what her subject has done to the portrait, but she can’t erase any new marks. The finished portrait is signed by Lehrer and her collaborator.

Lehrer, who has written about portraiture as a tool of power throughout history, says, “What does it mean to stare at someone for whom being looked at is often traumatizing? I wanted to make myself vulnerable the way my subjects are, to feel that loss of autonomy. The process is often painful and frightening. Sometimes, the person won’t make marks, because that means being exposed.”

Empathy is a key part of Lehrer’s political artworks, and her work illustrates how empathy pervades both art-making and the experience of looking at art.

What does it mean to stare at someone for whom being looked at is often traumatizing?”

The Center for Building a Culture of Empathy describes empathy as four spokes on a wheel: self-empathy, or mindfulness of what’s going on inside oneself; mirrored empathy, meaning taking on another person’s emotion; imaginative empathy, which involves putting yourself in another person’s shoes; and empathic action, i.e., contributing to the well being of others. All of these aspects can play a role in art-making.

In the 1800s, philosophers of aesthetics wondered why art brought people pleasure, and they came up with the idea that art triggers viewers’ memories and emotions. So, empathy was the mysterious element that connected art and the viewer. In 1873, German aesthetics student Robert Vischer described this projection of emotion as einfühlung, “feeling into,” and, in 1909, British psychologist Edward Titchener translated the word into English as “empathy.” Freud argued that psychoanalysts should embrace empathy in order to understand their patients

Joe Behen, PhD, Executive Director of Counseling, Health, and Disability Services at SAIC, observes, “Artists, as a whole, are more empathic than non-artists. They’re more sensitive. They tend to have more fluid, permeable personal boundaries that allow them to connect to people in meaningful, emotional ways. That connection provides fuel for the creative process.” Walter Osika, MD, PhD, Associate Professor at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, is doing research on the connection between burnout and compassion, which is defined as the action that results from empathy. He adds, “Artists can increase empathy in others through their work, eliciting

that feeling from people who may be numb from all the terrible things going on in the world, making the viewer more sensitive and vulnerable.”

Lehrer’s work partly involves “mirrored” empathy—i.e., recognizing and relating to others’ emotions—while fiction writers are often employing “imaginative” empathy, by putting themselves in their characters’ shoes. For SAIC Professor of Writing Jesse Ball, empathy is an integral part of his process. He has written numerous books, including novels and poetry collections.

“Artists try to make a gift of what they have felt,” he says. “What they have felt is the aggregate of what they have seen, and so it includes their own imaginings of what others have thought and felt.”

In his 2014 novel, Silence Once Begun, his narrator is an eponymous journalist who is suffering over a failed marriage. The fictional Jesse Ball tells the story of a salesman in a fishing town in Japan who confesses to a crime he did not commit and, in a failure of the justice system, bears imprisonment, refusing to speak. The journalist tells the story as an act of empathy, bearing witness to the man’s plight. In 2014, in the Paris Review, Ball said of using his own name in the book, “It’s an attempt to reconcile my experience of painful events in my own life with the world that I hope exists, a place where a person can have a meager place and not be sent away.”

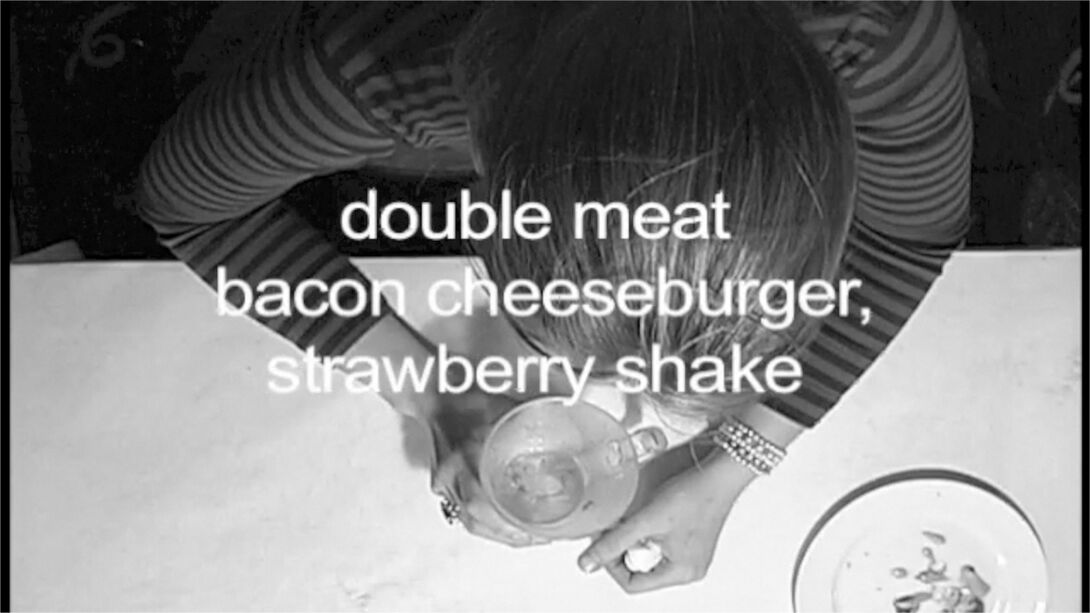

Then, there’s art that involves empathic action, and part of that is calling viewers’ attention to social or political issues. Since 2006, the Chicago-based art collaborative Lucky Pierre has re-created hundreds of final meals of death row inmates in Texas, which they found listed on the Texas Department of Criminal Justiceʹs website, as part of a massive, ongoing performance and black-and-white film project, Final Meals. The group has traveled to different cities—including Detroit, Portland, Berlin, and Hamburg—inviting the public to participate in the project by signing up for a meal, without knowing what it will be. Then, each participant receives a meal in solitude and is filmed from above; he or she can eat the meal, or just simply sit there. Compiled footage from these sessions has been shown in several galleries.

Kevin Kaempf, a member of Lucky Pierre and an Adjunct Associate Professor of Sculpture at SAIC, says, “We found the list on the website to be a strange proclamation of efficiency. So, we wanted to focus on the element of humanity and the conditions in our society that brought people to this moment—the conditions in which people aren’t taken care of, and then the state ultimately takes care of them.”

In addition to empathic action, Kaempf says the project also involves mirrored empathy: “I think the participants gain insight into a feeling of comfort for the inmate, because the meal requests clearly come from a memory—perhaps because a meaningful person prepared that dish for the inmate in the past.”

Artists can increase empathy in others through their work, eliciting that feeling from people who may be numb from all the terrible things going on in the world, making the viewer more sensitive and vulnerable.”

For these artists, empathy doesn’t have clearly defined boundaries; though there are four defined types, there’s much overlap. Ultimately, making art in an empathic way seems to require a certain vulnerability on the part of the artist (and, in the case of Final Meals, the participants as well). According to Ball, artists are constantly “re-feeling” emotions they have felt before or observed in others.

“Most of us are taught in our lives to conceal, rather than reveal, what we’ve felt,” he says. “But for artists, it’s as if they’re constantly breaking ice on the surface of a lake. To me, there is no real separation in the arts, between writing, visual art, et cetera. They’re all a gift of what has been felt and seen, as it is incarnated in some momentary form.”