Appetite for Disruption

“Art will continue to remain on the entertainment pages, peripheral to society, unless artists take their rightful place along with scientists in molding our new information architecture and language content. ” —Sonia Landy Sheridan, “Generative Systems Versus Copy Art: A Clarification of Terms and Ideas,”Leonardo, spring 1983

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s (SAIC) Department of Art and Technology Studies was the first of its kind in the country. It was created by merging the areas and interests of two visionary artists who began working at SAIC in the 1960s, Professor Emerita Sonia Landy Sheridan and Professor Emeritus Steven Waldeck.

Software and Hardware

Sheridan and Waldeck explored emerging technologies and were dedicated to disrupting traditional modes of art making. The story of this radically innovative department begins with an industry partnership between Sheridan and 3M Corporation that drew the attention of the school administration. At the same time, SAIC hired Waldeck, who had been working with technology and kinetics in his art practice since he was an undergraduate student. Sheridan’s curriculum dealt with the underlying systems, while Waldeck’s technical abilities tended toward the physical construction of technological forms.

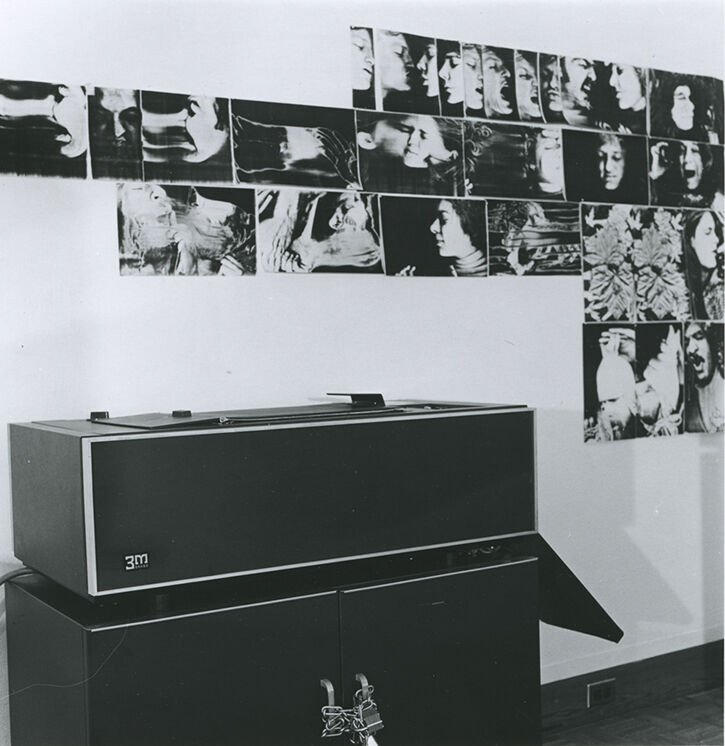

Sonia Landy Sheridan: I found a 3M Thermo-Fax, and the story with 3M begins. The use of the office copier had to do with trying to pass “art” to people on State Street to counteract the political posters that we were doing.

Steven Waldeck: In 1969 SAIC consisted of mostly traditional art areas. I was interested in expanding the concept of art by investigating new technical areas. My own art had taken that direction…. Although there were other jobs elsewhere, SAIC seemed the most open to new ideas.

Sheridan: In 1970 the energy and interest that surrounded the presence of industry in SAIC resulted in my being asked if I wanted a class in “reproduction.” I said, “Not under that name. We are reproducing nothing. We are creating images and discovering ideas never seen or known by us before.”

We became Generative Systems, in which the courses and ideas evolved with the science and the technology. That single class quickly grew, and we acquired graduate students, who became teachers as well as students.

Waldeck: I built the first “sensorium” [an immersive environment that engages all of the senses] at the school and wired it for experimentation by students with the help of my wife and assistants. This concept was rebuilt again in newer construction areas of the school throughout the years. At first, students had to use their own resources for their work (hand tools, etc.), and I did the same.

In 1972 Generative Systems became a complete graduate program, encompassing the study of any and all technologies—manual, mechanical, electronic, or biologic.

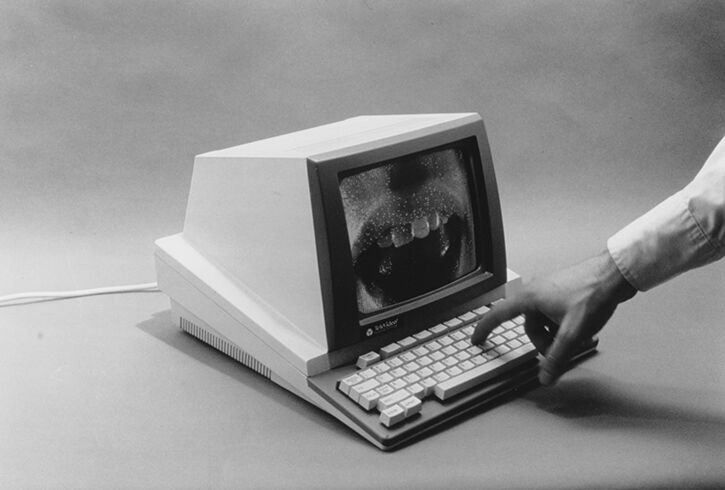

Sheridan: About 1977 Generative Systems graduate student John Dunn (MFA 1977) assembled our first image-making computer, with an algorithmic software that he created. The images were lovely, mathematical, moving shapes. John trained at least 10 students, and continued to return to teach students after graduation.

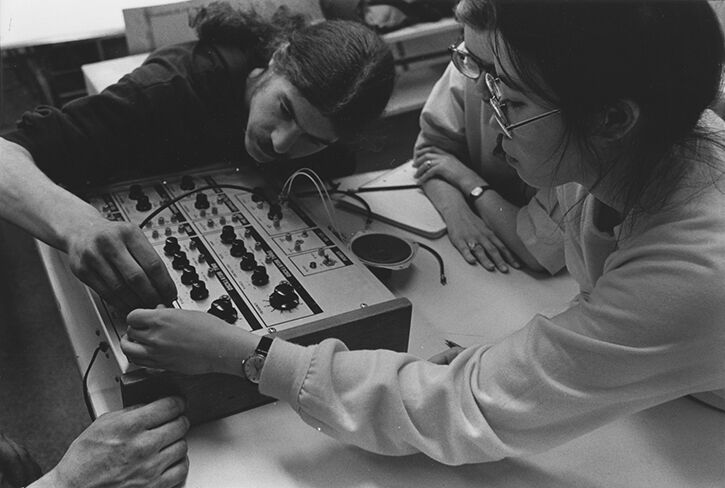

Waldeck: My philosophy was to offer technical assistance to any students from any area of the school. As an interest in “sound” grew, and a school budget finally appeared for supplies, I bought a sound synthesizer called a Putney for my area. I also developed and built an electronic sound synthesizer of my own, called Waldeck.

Eventually, the interest in sound became too overwhelming for me to handle, so I asked Dean [Roger] Gilmore to consider hiring someone to handle this direction, and the SAIC Sound area was born. My area of kinetics also experimented in light and explored neon and holography, later to become separate entities. The Time Arts area was created at SAIC as a response to my written proposal sent to Dean Gilmore outlining and defining this conceptual area.

Sheridan: Frequently I wrote that the technologies would come and go, only the people remained a constant. Generative Systems allowed for constantly developing technologies. Some technologies might become photography, some might evolve into video, and some would evolve into as yet unknown areas.

Waldeck: Sonia and I both had our own directions and both established a unique path. We were there in the beginning, but neither of us could have predicted the growth or development of SAIC throughout the years.

Art and Technology Studies

In 1980 Sheridan devoted herself full time to her own art practice. During her time at SAIC, she had received a Guggenheim Fellowship and three National Endowments for the Arts Grants. She created a program and curriculum that would inspire similar programs at institutions of higher education around the globe.

In 1981 Dean Gilmore asked Joan Truckenbrod (MFA 1979), a graduate student of Sheridan’s, to teach at SAIC. Truckenbrod enthusiastically accepted. In 1982 the Generative Systems program was renamed Art and Technology Studies by SAIC alum and Associate Professor John Manning (MFA 1981), with Truckenbrod as the Chair. In 1983 current Art and Technology Studies Chair Peter Gena joined the department.

Joan Truckenbrod: Art and Technology never accepts the boundaries… . The makers, producers of [technology] tell you how it’s supposed to work and what you’re supposed to do with it. The mission and goal of Art and Technology is to say: “ We’re going beyond; we’re going to do something else; or we’re going to put it in the tree and do this.”

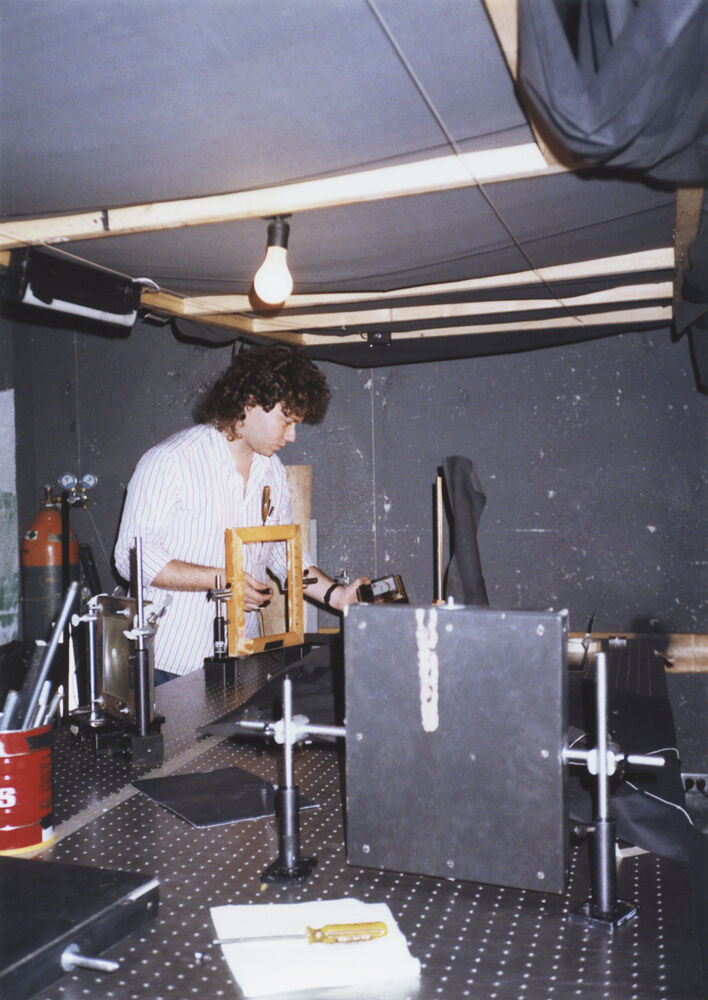

We had a graduate student, Eduardo Kac, who was doing holography and wanted to incorporate the computer. My perspective on developing the department was, when you find someone with insight, idea, and intelligence—the ability to do something—you support them. So we wrote up the course and created Computer Holography.

Eduardo Kac (MFA 1990, current Professor at SAIC): We did a lot of interactive, experimental work. For example, I worked with Ed Bennett, also a key figure in the history of the department, to develop telepresence. It was so radical, so innovative, so different. Many years later, you see younger artists using telepresence in their art, completely unaware of this history. And with digital holography, it’s the same thing. Holography to this day is not so well known.

Peter Gena: In my 46 years of using computers in my work I’ve always respected the computer as a partner in decision making. Rather than use the computer as an extension of a paintbrush, synthesizer, or typewriter, it is actually involved in decisions through use of algorithms that involve choice making.

When I first started, there was no software. If you wanted to use the computer, you had to write the program yourself. We still think programming is essential.

1990s: Bio Art is Born, Digital Expands

In the 1990s Professor Tiffany Holmes (now Dean of Undergraduate Studies at SAIC) joined the Department of Art and Technology Studies, bringing with her an interest in eco-art and sustainability, and Professor Shawn Decker, who creates sound and electronic media installations, was hired. In 1997 Kac returned to SAIC as a professor, a position he holds today.

In 1998 Kac wrote a manifesto in the journal Leonardo titled “Transgenic Art,” in which he explains the kind of bio art he would develop from that point onward. Kac’s own work, as well as his courses at SAIC, began to move down this radically new path.

Kac: In 1999 I presented my first transgenic work called Genesis, in which I collaborated with Peter Gena, my colleague in the department. I asked Peter to write music for Genesis. To do so, he used a computer program that he wrote in which he incorporated my Genesis DNA sequence as well as the mutation rate of E. coli bacteria.

At that point, I started to develop a bio lab in a small room in the back of the fourth floor [of the MacLean Center]. I hired a grad student to assist me in building a structure that we’d be using as an incubator, and we ran some bacterial transformation tests. The Dean at the time was Carol Becker, and she was very supportive.

When something is truly innovative, it’s not uncommon for the initial response to be one of shock and rejection. That is what happened with this early phase in the development of the bio art program. Bio art was very, very new. It had zero historical precedence, and there was a general lack of support at that time for the continuation of the program, which made it difficult to implement it.

Gena: The ’90s is when the department started spreading out. We increased programming, we introduced bio art and a fundamentals course that exposed students to all these separate disciplines. The ’80s were the formation, the early ’90s were the adolescence and the late ´90s the maturity.

2000s and Beyond

Today, Art and Technology Studies students can study: experimental visualization and fabrication; performative objects and responsive environments; bio art; embodied networks; creative coding; open source; thinking, creating, and designing with light; virtual and augmented reality; hypertext; and the history and theory of art and technology studies. Recent hires include Assistant Professor Christopher Baker and Assistant Professor Heather Dewey-Hagborg.

Kac: Nearly 20 years later, bio art is a full-fledged field. Now that so much time has passed, and bio art is out there with everything else, that initial resistance is no longer there. This made it possible for us to hire a colleague who practices bio art [Heather Dewey-Hagborg], which is wonderful. It is a sign that times have changed.

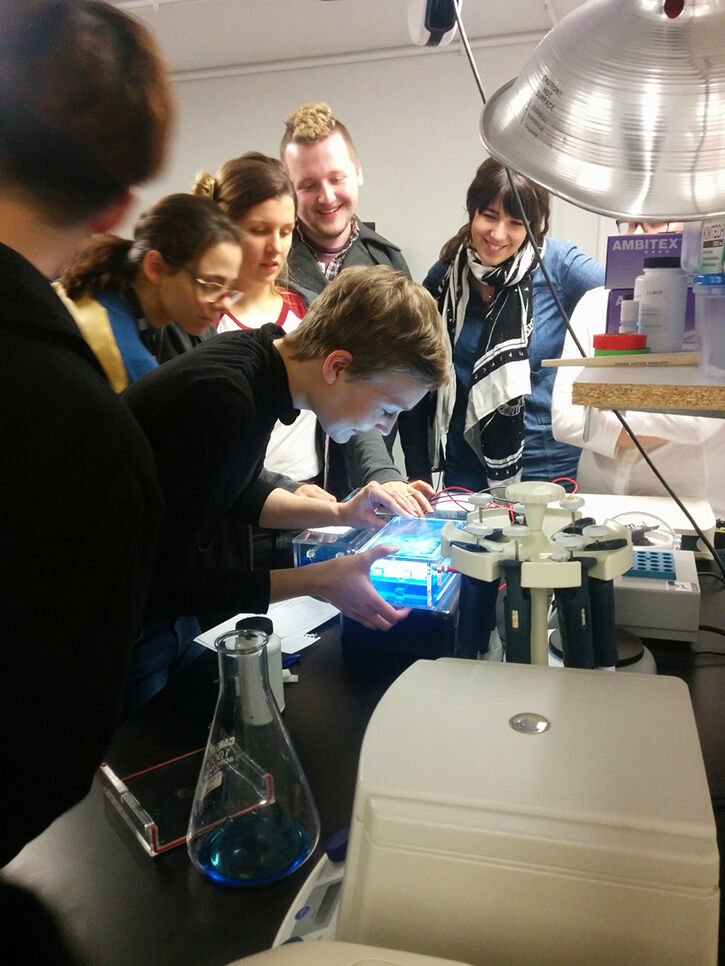

In spring of 2015 SAIC built a bio art lab where students use the tools and techniques of molecular and microbiology, including DNA extraction and analysis and synthetic biology.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg: The students I am interacting with are definitely interested in art-science practice. But there was a lot of interest in pushing boundaries of art and using new media when I was in school as well. I think the difference is the accessibility of tools and information and the saturation of popular culture with science and technology via crime shows, sci-fi, documentaries, and the news. I think we are really in a moment of obsession with science and tech right now in popular culture, so it is bound to influence what people want to make, explore, manipulate, and subvert.

Christopher Baker: A lot of what we like to imagine ourselves doing in the Art and Technology Studies department is thinking about the new technologies that are coming down the line and trying to engage them deeply enough that we can actually have some say in the larger cultural conversations about what those various technologies are for. A lot of what I do in my own work has to do with personal data, the kind of data you share whether you know it or not with Facebook, Twitter, and other corporations.

In his time at SAIC, Baker has won an EAGER Grant from the Earl and Brenda Shapiro Center for Research and Innovation to work with a group of students pushing the boundaries of a small, inexpensive computer called Raspberry Pi. With the help of energetic students, he also founded the Open Lab, a group interested in fostering open source, open hardware, and open data at SAIC.

Kac: The core mission of this department is not just to use this technology for a specific goal…. Technology is our medium itself. And technology is a receding horizon…a perpetually transforming material realm that as an artist you engage with.