About a Work

In the museum with Nenette Luarca-Shoaf

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)

by Zoya Brumberg (MA 2015)

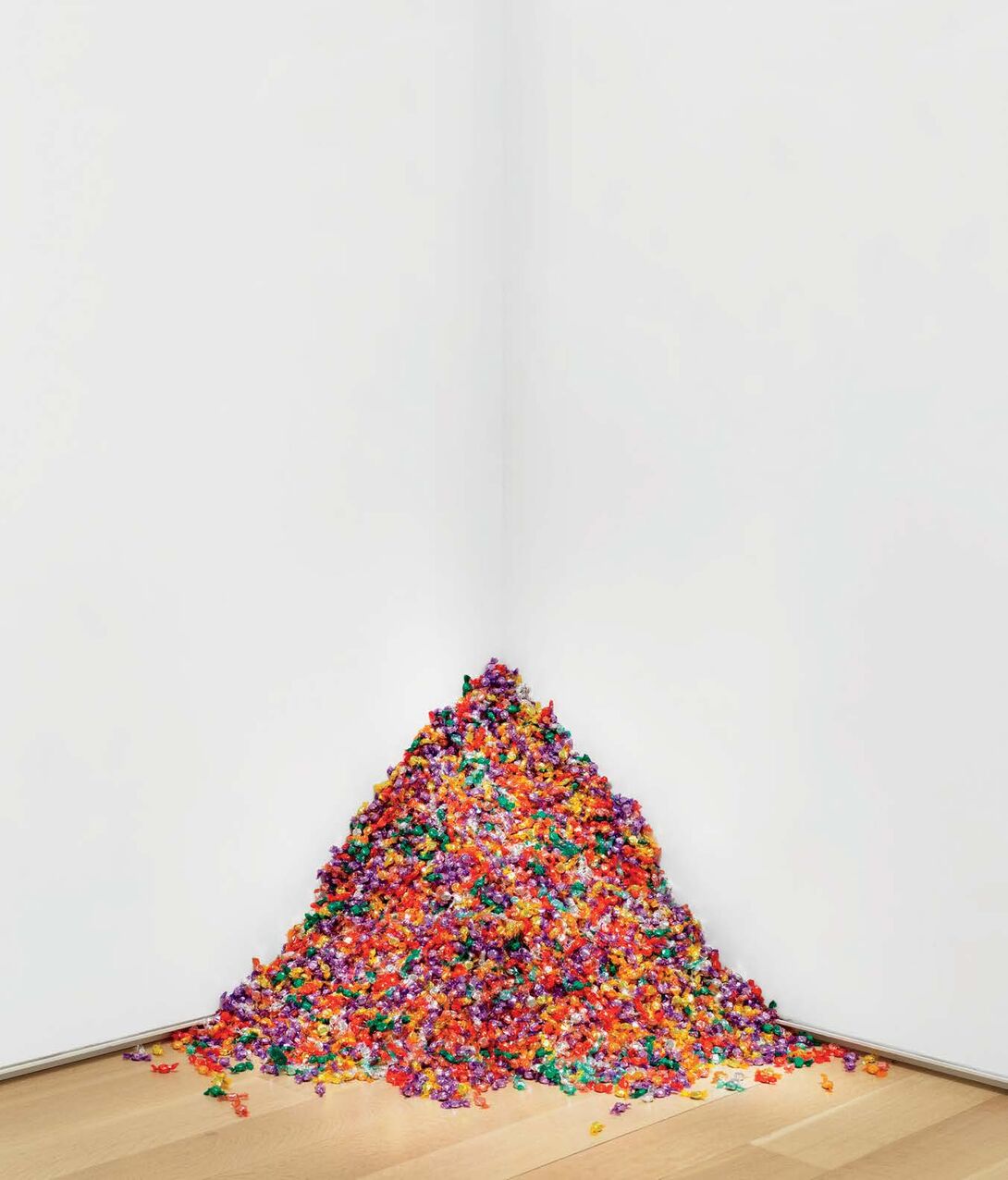

You reach your hand into the mass of candies piled in the corner of the Art Institute of Chicago museum gallery. You pull one out, running your hands over its smooth texture. As you bring it to your lips, its faint aroma awakens your senses before you taste its sweetness. You swallow more than just the candy; the other museum goers, the curator, the artist, and his lover all become a part of you.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) is no ordinary piece of art. One-hundred and seventy-five pounds of hard candies represent the weight of Gonzalez-Torres’ former lover, Ross Laycock, who died of complications of AIDS in 1991. Visitors to the gallery are invited to take pieces from the pile of candy; the loss of its weight mirroring the wasting away of a sickly body. The sweet and colorful joys of candy paradoxically express the artist’s pain of continuing to live beyond Laycock, though he too passed from the same affliction just a few years later in 1996.

According to Nenette Luarca-Shoaf, director of adult learning, associate curator of interpretation at the Art Institute of Chicago, and lecturer in the Museum Education Graduate Scholars Program, Portrait of Ross in L.A. is an intrinsically multisensory and participatory work of art. Every visitor to the gallery has the power to transform the work of art, the choice to take from it or leave it alone. You do not need to have an in-depth knowledge of the artist or art history to engage with the piece. As Luarca-Shoaf notes, “there’s always this kind of joy, common joy, that people have in being able to eat a piece of candy.”

The many layers of Portrait of Ross in L.A. make it an ideal example for Luarca-Shoaf’s lessons in object-based learning. She invites her students to “sift their hands in the pile and feel how heavy it is.” They take in the work with sight and touch, finding meaning in its placement on the ground and the visual impact of its brightness. They question what it means that “the weight of this work changes depending on how many people have taken the candy that day and that week,” and how that might be “a metaphor for the ideal weight of Ross, Gonzalez-Torres’ partner.”

Works like Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) exemplify the many ways that art expresses history while evoking personal feelings from its audiences. The “multisensory access of smelling and tasting and touching is a wonderful way to access memory, to reflect on one’s relationships over time and people that are important to you.”