About a Work

In the Museum with David Raskin: Cy Twombly, The Second Part of the Return from Parnassus

by Zoya Brumberg (MA 2015)

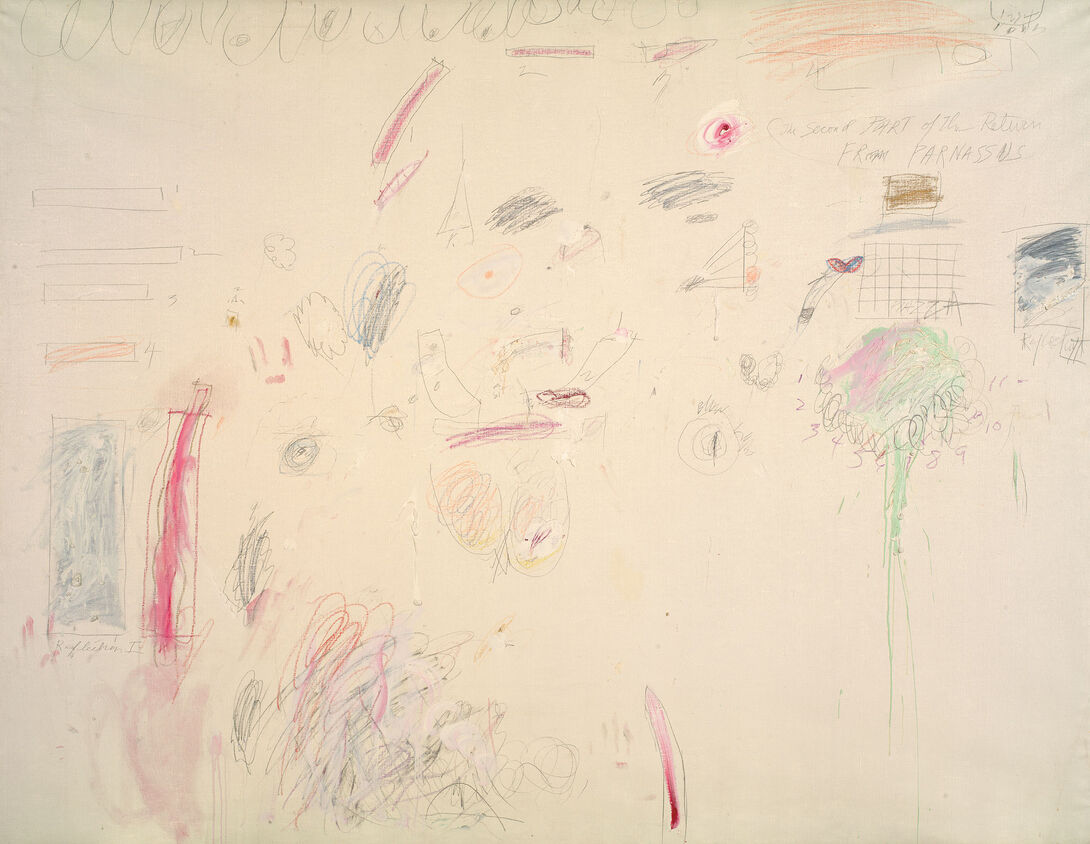

The Second Part of the Return from Parnassus, 1961, hangs in the 20th-century contemporary gallery of the Art Institute of Chicago just beyond Jackson Pollock’s emotive splatters and Mark Rothko’s abstract windows of color. The imposing size of the mostly bare canvas marked with seemingly unskilled lines evocative of children’s drawings is conspicuous among its neighbors. Set among Cy Twombly’s contemporaries, Parnassus forces Mohn Family Professor of Contemporary Art History David Raskin’s students to compare “what they think art should be against what they see before their eyes,” he says.

This challenge makes Parnassus one of Raskin’s favorite pieces in the Art Institute of Chicago to use in both his introductory and advanced art history classes. Students gather around the painting and see “all the rich details, all the specific qualities of each mark in relation to every other mark in a particular place.” The painting references methods and movements of art-making that students studied earlier in the course: pencil, crayon, thick globs of paint, linguistic text, numbers, scribbles, and nearly recognizable figures. Together in their exhaustive entabulation, they seem to undermine the idea that art can ever truly be expressive, leading students to ponder the very function of art after World War II.

Raskin wants his students to understand that art is not necessarily about aesthetic enjoyment or self-expression, but that it is always part of a discussion about what art is and what art should be. He sees Parnassus as a deeply cynical work, something that forces him to question the possibility of authentic expression or transcendence through art, our own human desires. Well-naturedly, he muses, “There’s value in having these illusions stripped from us. There’s no joy here. There’s only dismay and frustration with a tint of depression.”

Parnassus forces…students to compare “what they think art should be against what they see before their eyes.

David Raskin’s own search for the values of art fuels his curriculum in ways that he believes help his students—not only to become better art historians or better artists but to see the world more clearly. By testing their preconceptions against their own vision, young artists place their work into the most pressing conversations of the arts communities within SAIC and beyond.