Worth a Thousand Words

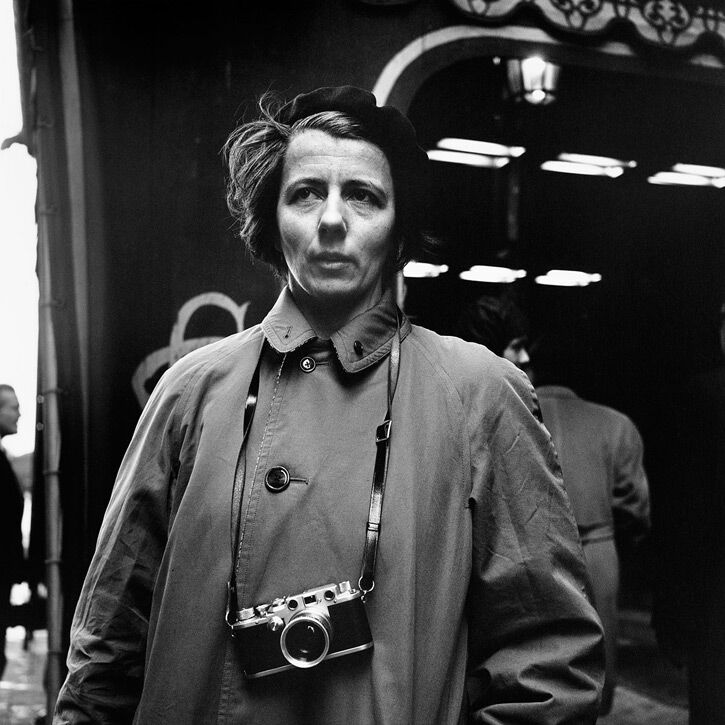

In April 2009, an 83-year-old woman died in Chicago—a city where she lived for 50 years. She was “a free and kindred spirit who magically touched the lives of all who knew her,” according to her obituary in the Chicago Tribune. But, as it turns out, not many people really knew her.

Photographer, filmmaker, and former real estate agent John Maloof was in the midst of a career change at the time. A few days before the obituary appeared online, he had opened a box of Vivian Maier’s belongings, which he bought at auction months earlier. He discovered rolls of expertly executed photographs, although he says he did not realize the mastery of the work at the time.

“I didn’t know anything about street photography. But what I saw in these images...was the city of Chicago in the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s—the historical perspective of it, he says. “And I got interested in documenting the city at the time.”

As Maloof began shooting and studying photography, he started to see similarities in Maier’s work to Eugene Atget, Lisette Model, and Diane Arbus. “I was thinking, ‘If they’re doing this, and they’re famous, then maybe she’s up there with that caliber of photography,’” he says. He tracked down other buyers of Maier’s belongings and bought as much as he could. With his own Rollieflex camera (the same kind Maier used) strapped around his neck, Maloof went to the Chicago Cultural Center and applied for an exhibition of Maier’s work.

Then he scanned some negatives and put them on Flickr to see what others thought. The images went viral. The Cultural Center accepted the application, and while he was working on the exhibition, Maloof was planning a book of Maier’s photographs and a documentary about uncovering her story, which was becoming increasingly complicated.

Maloof had been in contact with two men who said that Maier was their live-in nanny when they were children. They had placed the obituary. They believed she was from France. She was intensely private, and never spoke of her family. But she had been a second mother to them, and they cared for her as she aged. Maloof discovered that Maier was actually born in New York City, but spent time in France as a child before returning to New York. He found other families she had worked for with degrees of differing stories. Some complained of Maier’s newspaper hoarding, eccentricities, and at times mistreatment of her charges.

The success of the Cultural Center exhibition brought new people into the story. SAIC board of governors member and photographer Karen Frank remembers a friend calling her to tell her about a photography exhibition she had to see. Frank recognized the photographer as her children’s nanny in the late 1970s.

Like so many of the people Maier had worked for, Frank had no idea that Maier was a photographer. She contacted Maloof.

“I was stunned there was a woman who lived with me who had an entire life that I never knew anything about. She never seemed like a sensitive person. When you look at her photos, you see this woman had a great eye and was very sensitive to the human condition,” says Frank.

The press picked up the story, and friends of Howard Greenberg, owner of Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York City, began contacting him about Maier’s work. Greenberg usually does not work with posthumous prints, and Maier’s own prints were few and lacking in quality. He decided to visit Chicago anyway and meet with Maloof. After seeing the work and learning the story behind it, he became convinced that it deserved to be shown.

“From a purely visual-art level, she was enamored of photography...She understood the process of visual exploration and trying to make a good photograph and then make a better one,” says Greenberg. “She was actually quite a sophisticated picture maker.” Greenberg agreed to represent Maloof’s collection and engaged master printer Steve Rifkin to create silver gelatin and chromogenic color prints using Maier’s original negatives. The prints have been shown around the world.

For the documentary, Maloof teamed up with Charlie Siskel, an Emmy-nominated TV and film writer, director, and producer. Siskel says at first, the story drew him in. He saw elements of a buried treasure and mystery of a double life. But he also came to respect her as an artist.

“She certainly had an affinity for disenfranchised people—people on the edges of society. But also, her pictures of children are really beautiful. She seems to have an innate sense of the inner lives of children,” says Siskel.

The documentary Finding Vivian Maier screened at international film festivals and premiered at SAIC’s Gene Siskel Film Center and other theaters in March, playing to sold-out crowds. The success of the prints and film have been beyond what Maloof and Siskel imagined, and this year print sales repaid the costs of scanning and storing the archive. Maloof, Siskel, and Greenberg decided it was time to give back.

The three began by donating prints to charity auctions and making small monetary donations. But Maloof, Siskel, and Greenberg wanted to do something big. So they established the Vivian Maier Scholarship Fund at SAIC. Siskel says they wanted to lift some of the financial burden for young artists in school and chose SAIC because Maier often visited the museum and frequently saw films at the Gene Siskel Film Center.

This endowed scholarship will be awarded each year to a female student at SAIC with financial need. “This is a way to connect Vivian and her story to future artists,” says Siskel. “Because it’s an endowed scholarship, it’s permanent. And hopefully other people will contribute to it. This will be part of her legacy.”