Source/Material

by Jac Kuntz (MA 2016)

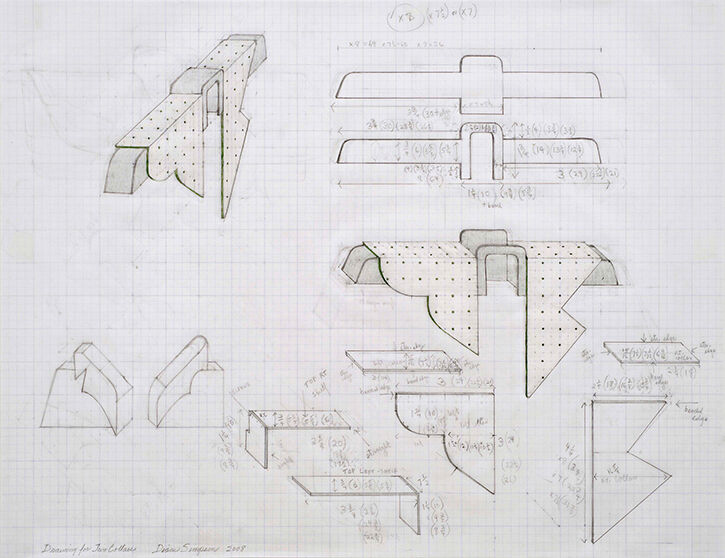

The sculptures of Diane Simpson (BFA 1971, MFA 1978) begin on the page before taking constructed form, referencing the human body, utilitarian objects, and architectural spaces. Experimenting with a wide selection of materials, such as wood, metal, linoleum, and fabric, Simpson finds intersections of culture, clothing, and space that reflect her interest in the coexistence of the industrial and domestic worlds. As part of the Visiting Artists Program’s Distinguished Alumni Lecture Series, Simpson will give an artist’s talk on Tuesday, April 5, 6:00 p.m. in the Art Institute of Chicago’s Rubloff Auditorium (230 S. Columbus Dr.).

How has working/living in Chicago—a city renowned for its historically and culturally significant architecture—influenced you?

My inspiration comes from the built world of objects, in contrast to the natural world. This preference possibly relates to my urban environment. The often-quoted dictums of two Chicago architects have influenced my work: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s “God is in the details,” and Louis Sullivan’s "Form follows function.” But my influences include a broad range of architecture and design—the work of Viennese architects, Otto Wagner and Joseph Hoffmann, Scottish architect/designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and traditional Japanese architecture.

Describe the conversation between fashion and architecture that you reference in your work.

In both fashion and architecture, I gravitate toward forms having simplified, strong silhouettes. I look for an integration and organization of related lines, patterns, and overall shape. In both architecture and fashion, I zero in on a section rather than the entire form—a collar or neckline of a garment, a chimney or window on a building.

Can you speak to the dichotomy of the domestic/private and the industrial/public found in both the aesthetic and thematic elements of your artwork?

My source images (clothing forms) have domestic associations, as do the materials I choose (linoleum, needlepoint mesh, upholstery webbing) and my fabrication techniques (stitching, weaving). But the public/industrial is also present. My drawings transform my sources into architectonic structures, which become associated with the public sphere as I incorporate industrial materials (wood, metal, rivets, etc.).

How did your time at SAIC shape your artistic practice?

During my high school years, I attended SAIC’s Junior School Life Drawing classes at the Art Institute of Chicago, and in undergrad at SAIC, I concentrated on figure drawing and painting. To this day, the human body is still present in my sculptural practice. It is a conscious presence, an invisible armature for my interest in body coverings.

Your sculptural practice was born out of a drawing style that systematically rendered three-dimensional utilitarian objects. How did you decide to actualize these drawings in large, sculptural forms?

In my last year of graduate school at SAIC, an advisor suggested I try building the very dimensional objects I was drawing since I thought of my attempts at sculpture as “drawings in space.” I named the first one Constructed Drawing.

I often apply the same visual principles that made sense in 2D to 3D. I trust my response to the drawing—if it holds interest on its own, and if it’s detailed enough to construct. A system or theme becomes apparent, and relationships develop between overall form and surface pattern; the width of an edge in the drawing can indicate the thickness of material required.