The Process

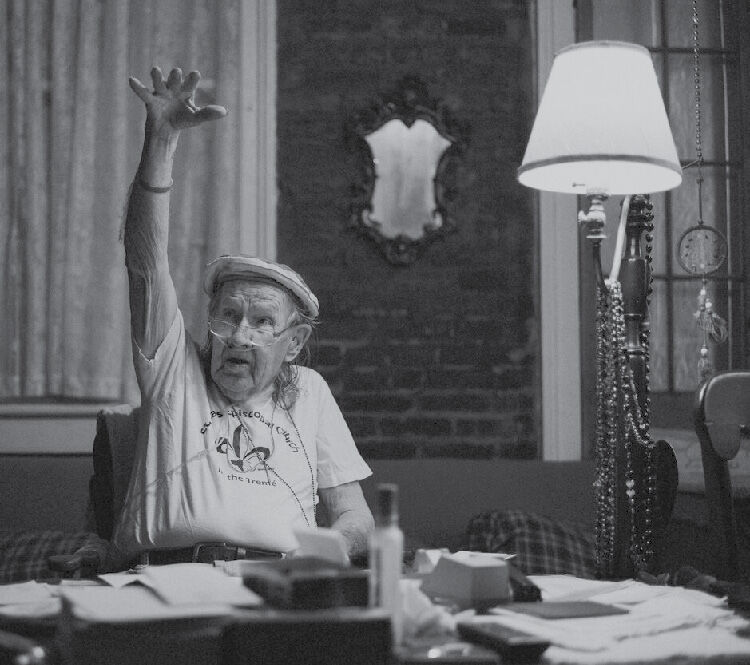

Robert Fieseler (Post-Bac 2005) on His Process

Poet-turned journalist Robert Fieseler (Post-Bac 2005) developed his lyrical style of nonfiction narration at SAIC. In his first book, Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation, Fieseler recounts the stories of the 32 people who died in an unsolved arson at a gay bar in 1973 New Orleans and the official silence in its aftermath that helped mobilize the gay liberation movement. It was the largest mass murder of LGBTQ citizens in US history until the Pulse nightclub shootings in 2016.

When Fieseler was a student at SAIC, Writing professor Amy England told the young poet he was “reporting” his poems and encouraged him to write nonfiction—advice that changed the path of his career. He followed SAIC with Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, where he wrote the proposal for Tinderbox.

“I’m a subculture reporter and a gay person,” says Fieseler. “I was actually a closeted gay man into my early 20s, so I knew emotionally what it meant to live in hiding…. I wanted to tell a story that would delve into that emotional terrain of what it was like when homosexuality was a big secret in America. We forget that it was once a secret subculture. I wanted to feature those generations of gay men forced to live in hiding, obliged to congregate and find love in clandestine havens like the Up Stairs Lounge.”

Once he had the interest of a publisher, he booked a flight to New Orleans. Fieseler tracked down survivors of the event and began the trust-building process required for them to recall the worst night of their lives. It was a night when many of the working-class men who escaped the flames were subsequently “outed” by media, which led to religious censure and family estrangement. For those unable to talk due to lingering trauma, or no longer alive, Fieseler turned to published accounts in newspaper archives. In all, his reporting developed portraits of nearly everyone who was in the bar at the time of the fire.

Fieseler’s writing process was disciplined. He determined that his golden hours for writing were between 10:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m., and he wrote through lunch to meet his daily quota of 1,200 to 1,500 words, then stopped. Continuing would steal the following day’s energy, breaking momentum.

“I’ve discovered that writers who have momentum finish chapters, and writers who finish chapters can finish books,” says Fieseler.

After writing, he’d check emails and do additional interviews to help get him out of his house. “Writing occurs in isolation, and I learned pretty quickly that cabin fever is real,” says Fieseler. He wrote the book sequentially, starting with the first line and ending with the last. His initial manuscript came in around 180,000 words, about the same length as Catch-22. He trimmed 2,000 words per day until he reached 90,000 words, shorter than Huckleberry Finn.

Rounds of editing, copyediting, and legal review followed until Tinderbox was released in summer 2018, four years after the work began. Fieseler spent the next several months promoting the hardcover and paperback on tour. Then he began the whole process again for his next book.