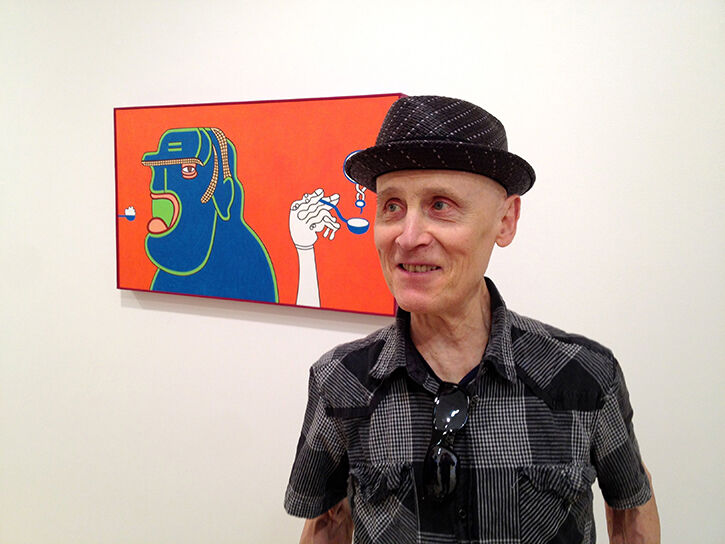

An Interview with Karl Wirsum

Karl Wirsum (BFA 1961, HON 2016), the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s (SAIC) beloved Professor of Painting and Drawing, was a member of the legendary arts collective the Hairy Who—a group of eccentric artists who began working together in the 1960s after meeting at SAIC. Wirsum collaborated with James Falconer (BFA 1965, HON 2016), Art Green (BFA 1965, HON 2016), Gladys Nilsson (BFA 1962, HON 2016), Jim Nutt (BFA 1967, HON 2016), and Suellen Rocca (BFA 1964, HON 2016) to found the collective. The Hairy Who and its impact on the Chicago art scene were celebrated at Commencement 2016, where each of the members received an honorary doctorate as part of the ceremony. Wirsum and his work with the Hairy Who came to be emblematic of the Chicago Imagist movement, a legacy exuded in the unconventional eye and vibrant personality he brings back into the SAIC community.

Why did you choose to attend SAIC?

I wanted to attend SAIC because as a youngster I took the Saturday classes. It was free, and I attended from ages six to nine. I had this association with the Institute, I was from Chicago, and I was granted a scholarship [for the degree program]. I received a scholarship, where I wasn’t paying anything, that took me all the way through the four years.

I knew I’d be a good fit. One of the great things about SAIC was the connection to Chicago and other world-class museums. If I went somewhere else, it would have taken me away from the dynamics of the city. I stayed in a YMCA on the Southeast side, which was right next to the Illinois central train.

Describe your work when you came to SAIC and how it progressed during your time at school.

When I first came, my work was similar to work in high school. My focus at that point was to be a cartoonist, and that’s initially why I wanted to be an artist. I realized that I had an ability to do other things as well. My real interest was pursuing a career within the comic industry in some way, either in a strip or via comic books like EC comics. They had war comics, horror comics, and humor comics—much like Mad magazine, which initially just satirized strips like Walt Disney and classic comic characters, taking hot shots at the entertainment and comics industries.

My first year in the program I took design, figure drawing, still life, and history of art. It was three studios and a history of art. Kathleen Blackshear, who taught history of art, had a dynamic approach, covering world art history, instead of focusing purely on Western art. She focused on different cultures: ancient Greece and Aegean cultures; Africa and early cultures in Meso-America; and Asian arts, East Indian, Chinese, Korean, and Japanese, etc.

I was exposed to different approaches as to what interesting, compelling art could be. Some approaches were stylized and 2D, some painting styles had graphic qualities, and some the traditionally Western, painterly style.

I discovered other possibilities for comics. I tried a fine arts approach, done in 2D styling. But in my four years, I did investigate textured surfaces and a more painterly approach that still worked around stylization. Surrealism, Dadaism, and some of the early modernist work influenced me, as well as the work of Klee, Picasso, and Matisse.

What was the curriculum like in the late 1950s to early '60s?

Kathleen Blackshear, in Art History, taught one class called Comp/Crit. It was similar to my childhood, weekend classes with a general focus on 2D, 3D, or line-based in some way on Bauhaus design elements.

I liked my design class my first year; it focused on stylistic outcomes. The instructor, Herman Graph, demonstrated with tempera paint and the idea of mixing a certain consistency of pigment to lay flat ground. That helped me in the years to come as I moved forward, and acrylic paint came into play (there’s a connection there with Mexican art and murals coming into vogue).

I also liked Dick Keen—I had him for still life. He was interested in literature, music, books, popular media, and the news. He had great knowledge on a variety of things, and it opened up other elements of culture to me, instead of focusing strictly on the visual. He expanded my vision, much like the history of art expanded my mind to what art could be.

I took a lot of figure drawing classes. I had an instructor my second year named Ms. van Paplin. She was a character, very enthusiastic. In those days, class was more formal, most people wore smocks, but she wore a see-through raincoat and galoshes. She didn’t critique as much as she generated enthusiasm. She would say: “keep on painting, keep on painting.” The joy of the visual experience is something I really took from her.

I also liked Vera Berdich, the etching teacher, an icon at the Art Institute. She was very eccentric and did her own work in class. She would work on her own plates and give you tips, but she did enthuse over people’s work, and liked what I was doing. I became her assistant and was able to access the studio more.

The late professor and artist Ray Yoshida (BFA 1953) is said to be a major influence on the work of the Chicago Imagists. Did you study with him?

I wasn’t in his classes, but I got to know him later. Whitney Halstead, an art history instructor who shared his philosophy, introduced me to Ray, so I knew him as an artist more than as an instructor. Later, because he taught people I became friends with—Phil Hansen and Jim and Gladys and Art Green—I did get an opportunity to get to know him.

Through the years, I was able to see his different apartments and his collections around the city. We shared an interest in Maxwell Street and a certain kind of visual phenomena. We had a personal, simpatico connection too. I, of course, also connected to his fantastic artwork and liked his responses in critique panels.

Would you consider SAIC an important part of your development as an artist?

I was interested in comics, which was more of a popular thing, but once I made the connection to fine art, it did change who I was. SAIC expanded my idea of what art could be; I learned more cultural possibilities. It was greatly formative, and I found instructors who were particularly good for me, as well as some that didn’t work out. For the most part, I had good experiences, and the teachers I took helped me out a great deal.

How did your access to the museum's collections as a student influence your work?

One of the things I was exposed to was the Print Department, where you can go in and check out the collection. Some of the people in that department showed us artists like Odilon Redon, who was very influential for me. I did like Seurat too—his drawings, big paintings, and stylization. I liked how he froze the figures and worked on paintings over an extended period of time—that sort of investment. I felt connected to the Japanese prints, too, because they were thought of as the Asian equivalent to comics in a way, because they were popular graphic media.

I liked El Greco’s elongated style as well. Some theories say he had a vision problem, that he didn’t see figures properly, and that the distortion is the way he actually saw things. But I liked his work. These are works I could look at in reproduction, see it in person, and translate what I saw in reproductive work (books and slides). I particularly like Matisse's work because he had a graphic element and linear quality. So there’s a wide range of things that were really good, and I still take students through the galleries, usually the first day.

After graduation, you, Ed Paschke (BFA 1961, MFA 1970, HON 1990), and Bert Phillips (BFA 1961) went to Mexico together. What was that trip like?

After the three of us graduated, we participated in a fellowship competition. Ed and Bert both won an award to go to Mexico. I had always wanted to go; I was very interested in Edward Weston and folk art tradition, masks, and ethnographic work, and of course the muralists. We didn’t go together, but we did meet up. [A mutual friend] had an acquaintance with an apartment in Mexico City, who split her time between there and San Diego. The friend suggested we live there and hold the fort down. It was really fun. She had these blank walls, and we did some murals. She came back to the surprise of her altered walls.