The Initiator

Political art inspires citizens

Tania Bruguera (MFA 2001, HON 2016) is running for president of Cuba. In an online video announcing her candidacy, she urges viewers in her native Spanish to reject fear and apathy and imagine a Cuba where they have the power to demand their rights. “Let’s start by proposing ourselves as potential candidates to the elections,” the English subtitles read. “Today I will start this exercise. I propose myself as a candidate for the 2018 elections. Propose yourself!”

The Republic of Cuba is, of course, a communist state in which current president Raúl Castro won 100 percent of the vote in the last election, according to the US Central Intelligence Agency’s World Factbook. While Castro has announced plans to step down from the presidency next year, his successor is widely believed to have been chosen already. But where others see insurmountable obstacles, Bruguera sees opportunity. She is not an artist; she is, in her own words, an “initiator.”

Bruguera’s art transforms her audience into engaged citizens. She proposes an idea, or initiates a piece, but “I recognize that the idea is going to change and be shaped by the people, by the community, and not by the desire of the artist,” she says. It’s easy to see why people are drawn to Bruguera. She has a warm smile and greets you with a hug upon meeting for the first time. So it’s not surprising that when she proposes a project, people join in. She initiates it, and her audience and those in power complete it.

A striking example of this idea is #YoTambienExijo, a planned restaging of Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (Havana Version). Presented in 2009 at the Havana Biennial, the work consisted of a microphone, loudspeakers, a podium, and a stage. Bruguera invited viewers to participate in one minute of free speech. In December 2014, she returned to Cuba to restage the performance in Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución. Her permit was denied, but she prepared to move forward. The day the performance was scheduled, she was detained by the government. The detention became part of the work, and the Cuban authorities who questioned her became participants.

Bruguera’s fearlessness in her art has earned her a spot on Foreign Policy magazine’s 100 Leading Global Thinkers list and the shortlist for the 2016 #Index100 Freedom of Expression Award. She won the 2015 Herb Alpert Award, served as a Yale World Fellow, and inaugurated the New York City Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs’ artist-in-residence program.

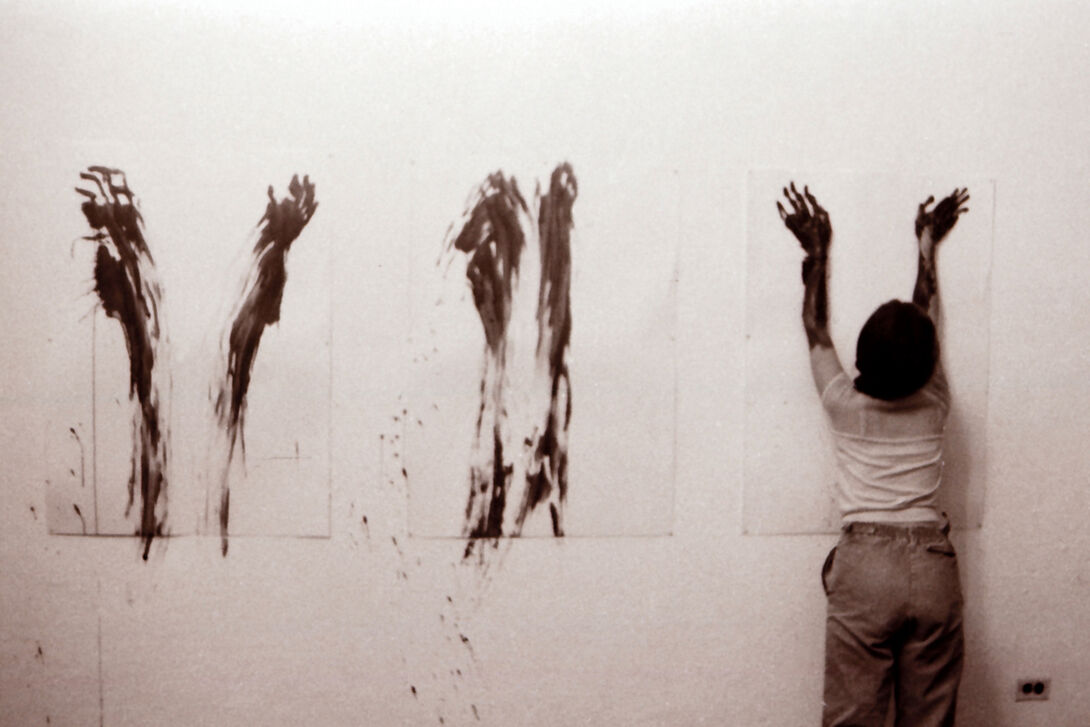

Before gaining international recognition, Bruguera began her career focusing on the work of another Cuban artist which was also shaped by the Cuban government: Ana Mendieta. Mendieta was exiled from Cuba two years after Fidel Castro came to power. In her most famous work, she traced her own silhouette into landscapes as a reaction to being torn from her homeland. From 1985 to 1996, Bruguera re-enacted Mendieta’s work in a series titled Tribute to Ana Mendieta. By 2000, when Bruguera was invited to participate in the Havana Biennial for the first time, her work had taken a more overtly political turn. She submitted Untitled (Havana, 2000), a large-scale installation inside a military facility. The floor was covered with decomposed sugar cane, and visitors walked through the darkness toward the glow of a television monitor playing public and private videos of Fidel Castro.

That same year, Bruguera applied for an MFA in Performance at SAIC. “I had acquired a little recognition in Cuba at the time, and I was feeling that I didn’t have real criticism of the work,” she says. SAIC challenged her identity as an artist and confirmed her shift from “performance” to arte de conducta, or art that uses social behavior as its material, and arte útil, which aims to transform society by using art to propose solutions to real problems.

These threads continue to carry through her work. Following her detention, Bruguera launched a Kickstarter campaign for her latest project, the Institute of Artivism Hannah Arendt (INSTAR) in Havana. Named for the German-American political theorist, this institute brings artists and activists from around the world to Havana to inspire ordinary Cubans to become active citizens by giving them space to freely deliberate the future of their country. Bruguera says, “It is about creating bridges of trust where there is no fear of each other, to create a peaceful and responsible response where there is violence, to create a place where people from different political views can come together to build a better country.”

When INSTAR was founded, the United States had begun to restore relations with Cuba. As the political climate shifts, and the communities of Cuban citizens and artists come together, Bruguera’s work begins to take form. In presenting Bruguera with an honorary doctorate in 2016, SAIC Professor Rachel Weiss described her process as one “in which she doesn’t know what will happen or what the work will finally consist of and mean until that emerges in the process of the work playing out. That means it’s a process that requires the courage to not know and to have faith in the people who become part of it.”

In a one-party state like Cuba, people can’t vote or demand their rights. Bruguera points out that in the United States, certain groups of people are excluded from democracy as well, and that’s where art comes in. In the face of uncertainty, and in a climate of fear, Bruguera remains fearless and bound to the idea that art can create a better world. “Art is a very effective tool for political change,” says Bruguera before leaving the interview to join a march for immigrant rights in Chicago.