A Critical Eye

by Brontë Mansfield (MA 2017)

Enrolling in art school is an act of courage.

“When I was a student, the goal of the faculty was to keep going until a person just broke down in tears,” art historian and SAIC faculty member Jim Elkins remembers of his MFA critiques in the 1980s. “People used to cry in front of the faculty all the time.” The tear-inducing critique—which Elkins documents in one of the only books on the subject—has become something of an art school cliché, like baggy black sweaters or a caffeine dependency. Critiques, even the difficult ones, can make an artist resilient, teach them to learn from failure, to be more human. Because criticism, both in school and outside of it, is so fundamental to an artist’s life, SAIC faculty members across disciplines are challenging and changing the way students approach this rite of passage.

Critique has become an essential part of art schools. As modernism and Bauhaus emerged, art schools shifted from developing technical skills to encouraging individual expression. The group critique as we know it was born. “Critiques are meant to challenge assumptions that the student is perceived to have,” Elkins explains. Students come into school with skills and ideologies that need to be unlearned, habits that need to be changed.

“I came through school when the perception was that you’re broken down and built back up again,” says Dawn Gavin, interim dean of undergraduate studies, who went to art school in Scotland. Gavin remembers “being horrified” by critiques as an undergraduate, but as a professor, has reoriented her relationship to them.

Now, Gavin oversees the undergraduate division, where students are first introduced to critiques. In her experience, two of the most useful things for students new to critique include the development of shared ground rules and an understanding of the attributes of emotional intelligence. While artists no longer need to have a breakdown to have a breakthrough, students should still be able to work through uncomfortable moments in their practice. Gavin likens critique to training athletes: “I think there are pain points when you make things and you care about them. Those are stretching moments. It really is that process of slight pain that you go through when you’re actually getting better at what you do.”

For novelist and Writing professor Jesse Ball, early sour experiences with creative writing workshops led to his invention of an entirely new critique process. “There I was in a series of workshop classes wherein the student provides work and is silent while others speak about it,” Ball remembers of his East Coast schooling. “To me the experience was often dreadful.”

Thirteen years ago, Ball and a friend created a method of critique called “Asking.” In this process, a student shares their work with a class and sits in front of the group. The group can only ask questions about the work, and they must avoid judgment, praise, and asking questions to which they know the answer. This turns the critique process into a playful competition among the group to come up with the most thought-provoking and meaningful questions.

“Something that Jesse Ball’s format gets at is that critique should be a way to learn what you think about your work,” says Brian Fabry Dorsam (MFA 2008). Dorsam took one of Ball’s classes as a graduate student. “The most useful thing for me is when a critique brings out a thought or a change to my piece that I didn’t know that I wanted to make. That’s why we engage people that we trust: to use their opinions to find our own.” As an alum, there are snippets from critiques that Dorsam hears like mantras in their head as they create art outside of school. When Dorsam needs to hear feedback now, they seek out the honest responses of the community that they built at SAIC.

Elkins gives similar advice to artists outside of schools: get a set of artist friends together to form a crit group but after a few years, have the courage to find new friends with new voices and fresh perspectives. The ability to absorb critical feedback and learn from it is a vital skill for any career—inside or outside of the art world.

The most useful thing for me is when a critique brings out a thought or a change to my piece that I didn’t know that I wanted to make. That’s why we engage people that we trust: to use their opinions to find our own.

Brian Fabry Dorsam (MFA 2018)

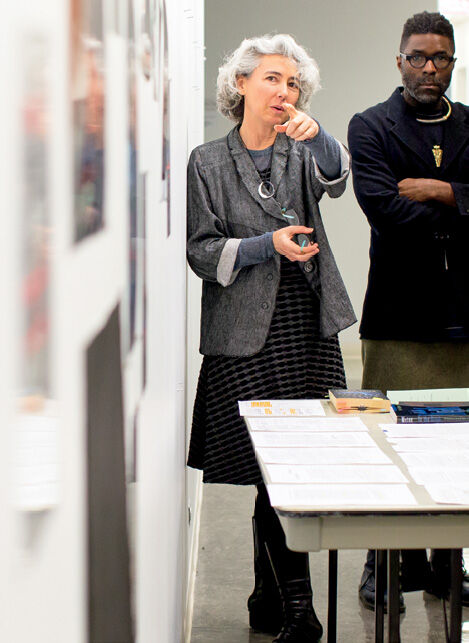

The Chicago Tribune art critic and SAIC faculty member Lori Waxman (MA 2001) devised a new method for critiquing work outside of art schools and publications: an ongoing performance art piece called 60 wrd/min art critic. Waxman travels to various locations to set up an office, complete with a computer, projector, and receptionist, to give artists a chance to have their work reviewed. Those seeking her feedback can bring a single work of art to her office where Waxman creates a 200-word review in 30 minutes.

Waxman has reviewed pieces by established artists and self-taught people who have never shared their art before, writing about everything from a priest’s conceptual landscape paintings to a singer’s performance. This up-close-and-personal experience, she says, has made her “a very human art critic. I have to work hard to forget that there’s an artist on the other side of the artwork.”

Perhaps as a reaction to the rough crit myth, many artists are fostering critiques that strike the balance between dread and empathy—which feels uniquely important in this cultural moment. And critique will continue to evolve in years to come.

“It’s as complicated and as messy and as wonderful as all human interrelationships,” Gavin says. “Critique is like a living thing.”