Charlie Pipal, Adjunct Professor

“If you have a piece of ephemera, like a paper or scarf or something, it’s just an object behind a glass case,” says Charlie Pipal, AIA, Adjunct Professor of Historic Preservation. “If you really want to get a feel for what it was like to be around at a certain time, historic built environments give you an interesting experiential aspect that objects don’t. It’s like a scarf that you can walk around in.”

Pipal brings this immersive view of the built environment into his pedagogy, his career as a restoration architect, and even into his personal life. Beyond his career-long commitment to preservation, Pipal and his family reside in Riverside, Illinois, a suburban planned community designed by Frederick Law Olmsted to be “the lungs of the city,” where he serves as the chair of the local Preservation Commission.

“It’s interesting to see [preservation] from both sides in that way,” Pipal offers.

In reality, Pipal has seen the field of preservation from a range of “sides” since earning his Master’s in Architecture from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Although he concentrated in preservation, documentation, and architectural history throughout his training, Pipal’s first job after graduation was measuring Chinese restaurants in Chicago’s Chinatown. Through a professional introduction, Pipal landed at the city’s Commission on Landmarks, where he was assigned to document 7 of the city’s 50 aldermanic wards in the nascent Chicago Historic Resources Survey.

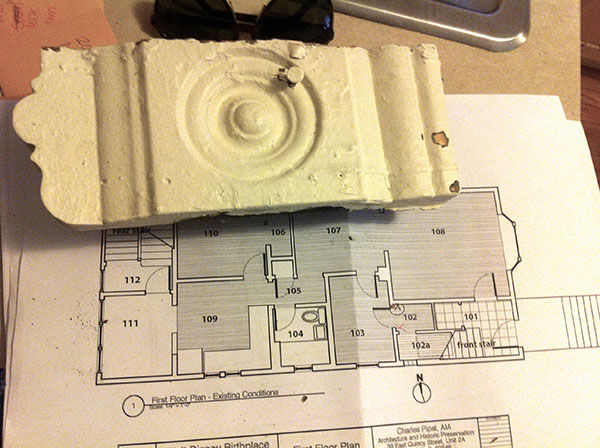

After staying on as a permit reviewer and later working for a private architecture firm, Pipal opened his own practice in 1998. In this role, Pipal has designed numerous additions to historic residences in the Chicago area, as well as special projects such as the restoration of the birthplace of Walt Disney, currently in progress in Chicago’s Hermosa neighborhood.

“With [the Disney house], I make every decision by asking myself whether Walt or his father would recognize the building.” Pipal’s work at the Disney house is guided by his own abiding interest in site interpretation and evolution, which likewise stems from his family’s longtime ownership of Blueprint Tours, a destination management company specifically focused on curricular-based travel to some of the most famous historic sites in the world.

Pipal’s personal and professional interest in historic site interpretation led to his development of an elective course first taught in the spring of 2015 called “Things Seen and Unseen.” In this class, students selected sites in Chicago where historic events occurred, but evidence of those historic events has been largely eradicated by development and progress (examples include the sites of the Eastland Disaster, Fort Dearborn, the Iroquois Theater Fire, the first controlled nuclear reaction, and Camp Douglas, a relatively unknown Civil War prison camp). Students researched their sites, and then designed interpretive tools in an attempt to present and preserve the memory of each event.

Pipal teaches a number of other electives, including Sustainability in Historic Preservation and Project Management, as well as two core classes. The first of these required courses, Physical Documentation Studio, requires students to measure and hand-draw historic buildings in Chicago or its suburbs, and final drawing sets are sent to the Library of Congress for preservation under the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS). The second core class, Preservation Planning Studio, hearkens back to Pipal’s time working on the Chicago Historic Resources Survey as a young professional. Since 2006, students in this course have surveyed buildings constructed between ca. 1930 and ca. 1970 in Chicago’s suburbs for inclusion in the Recent Past Survey of Suburban Cook County.

Although neither of these courses engage students in direct preservation methods, Pipal suggests that documentation is still an essential tool. “A lot of the time when you’ve done a documentation project for a building, and the building is altered or demolished, that HABS drawing might be the only record you have left. It’s a way of ensuring that a building is preserved in memory, at the very least.”

No matter which course he teaches, Pipal enjoys incorporating real-life sites in Chicago. The city serves as the backbone of many classes, with fieldwork and site visits featured prominently. “Chicago is unique for a student or even a lifelong lover of architecture. It’s probably without peer. It’s the quintessential American city,” Pipal continued. “The siting couldn’t be more dramatic – it’s on an inland sea, it’s carved by a narrow river, there are interesting bridges.”

Interestingly, Pipal himself has had an unforeseen but long-lasting impact on how the city’s distinctive bridges look today. Early in his career, Pipal was hired by the city of Chicago to conduct a survey of first-generation bascule bridges, which included photographic documentation, historic research, and writing a study outlining his findings.

“Six months later,” Pipal said, “Mayor Daley apparently went to Paris and was fascinated by all of the colors of the bridges there, and came back and said, ‘We have to do something about our bridge colors.”

Tim Samuelson, the Cultural Historian for the City of Chicago, called on Pipal to revisit his study and determine the original color for the city’s bridges.

“I went to the Municipal Reference Library where they had the original specifications books for the first-generation bridges. The books all gave the same color formula – a kind of warm reddish brown. I found an Illinois Department of Transportation color chart, chose the closest color, and wrote a memo about my findings. I left the city soon after that, but six months later, suddenly every bridge was ‘Charlie Pipal Brown!’”

Story by Monica Giacomucci (MSHP, 2015)